The Perils of Bypassing the Democratic Process: A Lesson in Governance

The Fall of "Liberation Day" Tariffs: Implications for Trade, Politics, and Global Affairs

A Radical Blueprint to Transform New York City into the World’s Greatest Metropolis

Economies Poised for High Growth

India’s Chances of Achieving Double-Digit Growth Rates

China’s Governance Model: A Case for Meritocratic Efficiency

St. Louis Renewal

Components Of A Sane Southern Border

"US court blocks Trump's 'Liberation Day' tariffs"

The situation with President Donald Trump’s tariffs involves a complex interplay of judicial rulings, executive authority, and congressional roles, reflecting ongoing tensions over the separation of powers in U.S. trade policy. Here’s a breakdown of what’s happening, the judicial process ahead, and the role of Congress, based on recent developments and the broader legal context.

- U.S. Court of International Trade (USCIT):

- The USCIT’s May 28 ruling was a decision on the merits in two consolidated cases—one brought by 12 Democratic-led states (e.g., New York, Oregon) and another by five small businesses (e.g., V.O.S. Selections). The court issued a permanent injunction, declaring the tariffs illegal and ordering their cessation. This ruling applies broadly, not just to the plaintiffs, because the tariffs were deemed “unlawful as to all.”

- The administration immediately appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit and requested a stay, which was granted on May 29. The USCIT could still be involved if further procedural motions arise, but the focus has shifted to the appellate level.

- U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit:

- The Federal Circuit, which has jurisdiction over USCIT appeals, issued an administrative stay to allow time to consider a longer stay pending appeal. The court has set a briefing schedule (plaintiffs respond by June 5, administration by June 9), after which it will decide whether to maintain the stay or let the USCIT’s injunction take effect.

- The Federal Circuit will then review the merits of the USCIT’s ruling, focusing on whether Trump’s use of IEEPA was lawful and whether the tariffs align with constitutional and statutory limits. This process could take several months, depending on the court’s docket and the complexity of the case. Oral arguments and a written decision would follow.

- If the Federal Circuit upholds the USCIT’s ruling, the tariffs would be permanently blocked unless the administration appeals further. If it overturns the ruling, the tariffs could proceed, though plaintiffs could appeal to the Supreme Court.

- U.S. Supreme Court:

- If either party loses at the Federal Circuit, they are likely to appeal to the Supreme Court, which has discretion to take the case. The administration has already signaled it may seek emergency relief from the Supreme Court if the Federal Circuit does not maintain the stay.

- The Supreme Court could issue an emergency stay or injunction to preserve or halt the tariffs while it considers whether to hear the case. If it takes the case, a ruling could address broader questions about presidential authority under IEEPA, the nondelegation doctrine (whether Congress improperly delegated tariff power), and the major questions doctrine (whether major economic policies require clear congressional authorization).

- A Supreme Court decision could take a year or more, though expedited review is possible given the tariffs’ economic and diplomatic impact. A ruling would likely be final, unless Congress passes new legislation to alter the legal framework.

- Parallel Litigation:

- Other lawsuits, like the D.C. District Court case, are proceeding in parallel. These may be consolidated or transferred to the USCIT, which has exclusive jurisdiction over tariff disputes. The outcomes of these cases could influence the main appeal but are narrower in scope (e.g., applying only to specific plaintiffs).

- If the Supreme Court limits nationwide injunctions (a separate issue the administration is pushing), it could complicate relief for plaintiffs, requiring individual importers to file separate lawsuits.

- Constitutional Role and Delegation:

- The Constitution explicitly grants Congress the power “to lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises” and to regulate commerce with foreign nations (Article I, Section 8). However, Congress has historically delegated significant trade authority to the executive branch through statutes like IEEPA, the Trade Act of 1974, and the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. These laws allow the president to impose tariffs under specific conditions (e.g., national security, trade imbalances), often with minimal congressional oversight.

- The USCIT’s ruling emphasized that IEEPA does not grant “unbounded” tariff authority, reinforcing that Congress holds primary power. However, Congress’s delegation of authority in IEEPA and other laws has created ambiguity, enabling presidents to act unilaterally unless challenged in court.

- Political Dynamics:

- Congress is deeply polarized, and Trump’s tariffs are a divisive issue. Many Republicans support Trump’s “America First” trade agenda, viewing tariffs as a tool to boost U.S. manufacturing and counter foreign trade practices. Democrats and some Republicans (e.g., Sen. Rand Paul) oppose the tariffs, citing their economic harm to consumers and businesses, but lack the cohesion or votes to pass legislation overriding them.

- Passing new trade legislation or revoking Trump’s tariffs would require bipartisan agreement and potentially a veto-proof majority (two-thirds in both chambers), as Trump could veto any bill limiting his authority. With Republicans controlling the House and Senate in 2025, such a move is unlikely.

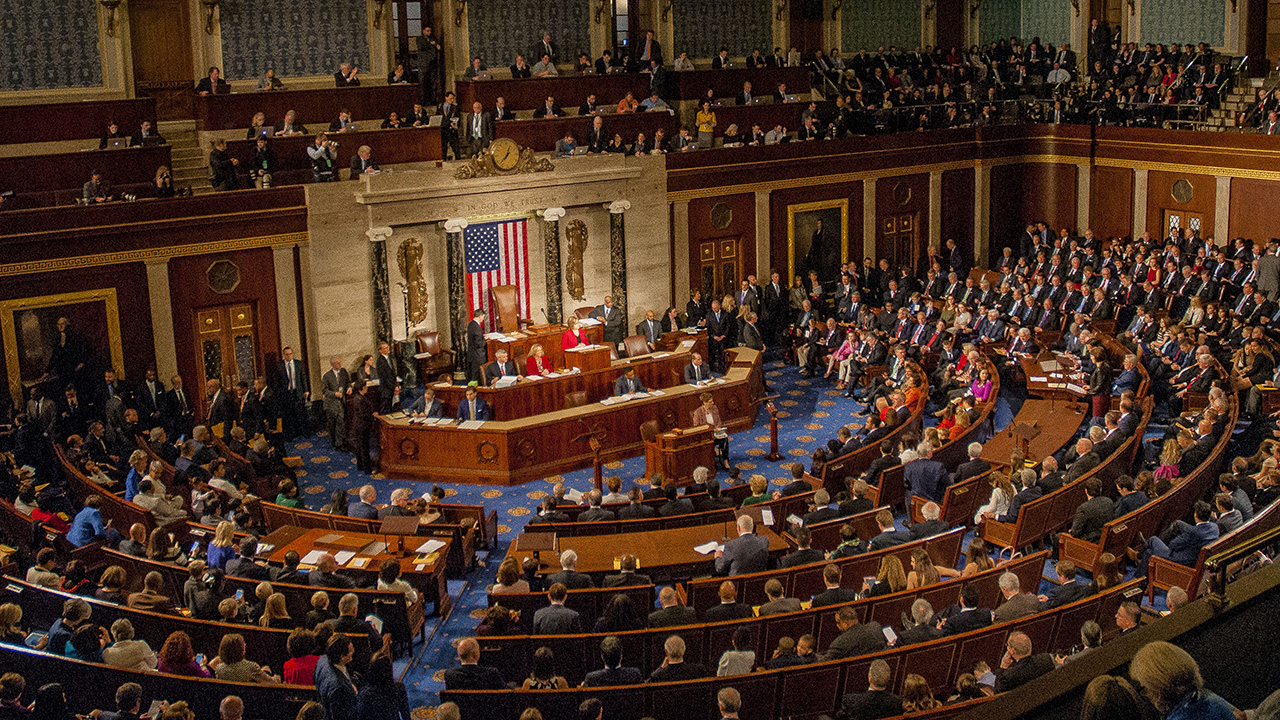

- Trump’s tariffs were imposed via executive action, bypassing Congress entirely. This reduces the immediate need for congressional action, as the judiciary is currently the primary check. Congress could theoretically pass a law to reinstate or block the tariffs, but political gridlock and the complexity of trade policy make this improbable in the short term.

- Practical Considerations:

- Congress moves slowly due to its deliberative process, committee structures, and competing priorities (e.g., budget negotiations, immigration). The tariffs’ rapid implementation and judicial challenges have outpaced Congress’s ability to respond legislatively.

- Some lawmakers may prefer to let the courts resolve the issue, avoiding the political risk of taking a stance. If the courts ultimately strike down the tariffs, Congress avoids a contentious fight. If the tariffs are upheld, Congress can revisit the issue later with clearer legal guidance.

- Should Congress Be Active?:

- From a constitutional perspective, Congress should be active, as the USCIT’s ruling underscores that tariff power belongs to Congress. The nondelegation doctrine, cited by the court, suggests that Congress cannot delegate sweeping legislative authority to the executive without clear limits. A decision against Trump could prompt Congress to clarify IEEPA’s scope or pass new trade laws to reassert control.

- However, Congress’s inaction reflects a broader trend of ceding trade authority to the executive, a practice dating back decades. Reversing this would require significant political will, which is currently lacking. Critics argue that Congress’s passivity allows presidents to exploit vague statutes like IEEPA, undermining the separation of powers.

- What’s Happening: The USCIT struck down Trump’s tariffs on May 28, 2025, for exceeding IEEPA authority, but the Federal Circuit reinstated them temporarily on May 29 via an administrative stay, pending appeal. This reflects ongoing legal challenges to Trump’s executive actions.

- Judicial Process: The Federal Circuit will review the USCIT’s ruling, with briefs due in early June 2025. A decision could take months, followed by a likely Supreme Court appeal, which may not conclude until 2026. Parallel lawsuits add complexity but may consolidate under USCIT jurisdiction.

- Congress’s Role: Congress has the constitutional power over tariffs but has delegated significant authority to the executive. Political polarization, procedural delays, and reliance on courts explain its inaction. Congress could act to clarify or limit presidential trade powers but is unlikely to do so without a clear judicial or public mandate.

No comments:

Post a Comment