Pakistan–Afghanistan Border Clashes of 2025: Anatomy of a Modern Frontier War

Introduction: The Durand Line Reignites

In early October 2025, the long-simmering tensions between Pakistan and Afghanistan exploded into open warfare — the most serious confrontation since the Taliban seized Kabul in 2021. What began as a targeted campaign by Pakistan against the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) quickly devolved into a volatile border conflict, engulfing regions from Kunar and Kurram to Chaman–Spin Boldak and Khyber.

The spark was familiar: Pakistan accused Afghanistan’s Taliban government of sheltering TTP fighters, while Kabul countered that Islamabad’s airstrikes violated Afghan sovereignty. Within days, artillery, drones, and ground troops were exchanging fire across multiple sectors. As of mid-October, both sides had agreed to a fragile 48-hour ceasefire — but the peace is tenuous, and the underlying grievances remain unresolved.

Historical Context: The Ghost of the Durand Line

The 1,640-mile Durand Line, drawn by British colonial officials in 1893, remains one of the world’s most contentious borders. Afghanistan has never formally recognized it, arguing that it unjustly divides the Pashtun people between two states. For decades, this dispute has fueled cross-border militancy, irredentist rhetoric, and proxy wars.

Pakistan, for its part, has often viewed the Afghan Taliban as a strategic buffer against Indian influence. But since the Taliban’s return to power, that calculation has backfired. The TTP — ideologically aligned with the Taliban but hostile to Islamabad — has staged increasingly lethal attacks in Pakistan’s northwest, killing hundreds of soldiers and civilians in 2025 alone. The result is a bitter irony: Pakistan now finds itself fighting those it once helped empower.

Timeline of the October Escalation

October 2–3, 2025 — Early Clashes in Kunar and Nuristan:

Gunfire erupted along the Durand Line in Kunar’s Nari district, with skirmishes spilling into Nuristan and Pakistan’s Chitral. Islamabad accused Kabul of harboring TTP fighters; Kabul retorted that Pakistan had provoked the fighting with unannounced air raids. At least three Pakistani soldiers were reported dead.

October 9–12 — Pakistan’s Airstrikes and Afghan Retaliation:

Pakistan launched widespread airstrikes on October 9, targeting alleged TTP safehouses in Kabul, Khost, and Paktika. Civilian casualties drew global condemnation. The Taliban responded with heavy ground assaults near Chaman and Kurram, reportedly overrunning several Pakistani outposts. Videos circulating online showed sustained gunfire lighting up the night sky as both sides traded blame for “unprovoked aggression.”

October 14–15 — Escalation and Ceasefire:

New clashes broke out in the Khyber and Zazai Maidan sectors, with Pakistani drones spotted near Kabul. At least 15 Afghan civilians were killed, prompting emergency evacuations in Helmand. Pakistani tanks reportedly crossed several miles into Afghan territory. By October 15, both sides announced a 48-hour truce, each claiming the other had requested it first.

Despite the ceasefire, sporadic shelling continued, suggesting that neither government fully controls its frontline forces.

Asymmetrical Warfare: Air Power vs. Ground Grit

The conflict exposes a deep asymmetry in military capabilities.

Pakistan’s Edge:

With one of the most capable air forces in the Muslim world, Pakistan has used drones and F-16s to conduct deep strikes inside Afghan territory. Its access to precision munitions, satellite intelligence, and electronic warfare gives it an undeniable technological edge. Islamabad justifies these operations as “defensive actions” against TTP hideouts, though Afghan officials and UN observers describe them as indiscriminate bombings that have killed civilians.

Afghanistan’s Response:

The Taliban government, lacking a functional air force, relies on infantry-based tactics — ambushes, mountain warfare, and improvised explosives. Many of its fighters are veterans of the 20-year insurgency against NATO, giving them an advantage in terrain familiarity and morale. Their ideology frames the conflict not as a border skirmish but as a defense of Afghan sovereignty and Pashtun dignity.

In the rugged borderlands, the Taliban’s decentralized command and guerrilla agility have occasionally outmaneuvered Pakistan’s mechanized forces. Reports suggest Taliban fighters have ambushed supply convoys, captured outposts, and forced Pakistani troops to retreat under pressure.

Reports of Pakistani Retreats and Battlefield Setbacks

Several independent journalists and open-source intelligence analysts have documented instances of Pakistani soldiers fleeing their posts.

-

October 11–12: Multiple Pakistani border positions in the Kurram and Chaman sectors reportedly fell to Taliban assaults. Videos shared on social media show Taliban fighters celebrating over captured posts, raising both Afghan and TTP flags.

-

Kunar Sector: Afghan units allegedly forced Pakistani and TTP combatants to withdraw from mountain positions.

-

Psychological Impact: Facing former Taliban allies has damaged Pakistani troop morale. The Taliban, exploiting this psychological edge, has portrayed itself as the true defender of Pashtun lands.

Islamabad has downplayed these reports, claiming to have recaptured “lost ground” and inflicted “heavy casualties” on the Taliban in counteroffensives. However, the fog of war and propaganda from both sides make independent verification difficult.

Geopolitical Dimensions: The Regional Chessboard

The Pakistan–Afghanistan conflict has far-reaching implications for South and Central Asia:

-

China’s CPEC Dilemma:

China, Pakistan’s closest ally, views border instability as a direct threat to the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Beijing has quietly urged de-escalation, fearing that expanded fighting could endanger infrastructure investments worth over $60 billion. -

India’s Strategic Calculus:

Islamabad has accused New Delhi of “fomenting unrest” by allegedly providing intelligence support to Kabul — a claim India denies. Yet Indian strategists see the conflict as weakening Pakistan’s western flank, potentially reducing pressure on Kashmir. -

Gulf States and the U.S.:

Qatar and Saudi Arabia have offered to mediate, reflecting their influence with the Taliban leadership. Washington, wary of further regional instability, has called for restraint but avoided taking sides, given Pakistan’s nuclear status and Afghanistan’s isolation. -

Iran and Russia:

Both countries view the clashes as evidence of U.S. and NATO’s failed exit strategy. Tehran, sharing borders with both, has increased patrols near Herat and called for an “Afghan-led dialogue.”

Could the Taliban Seize Khyber Pakhtunkhwa?

A question gaining traction online is whether Afghanistan could seize Pakistan’s Pashtun-majority regions, including Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP).

While emotionally resonant, such a scenario is implausible. Afghanistan’s economy is in ruins, its air force defunct, and its heavy weaponry limited. Pakistan, by contrast, maintains one of the world’s most powerful militaries, including nuclear capabilities. A full-scale Afghan offensive would likely invite overwhelming retaliation.

That said, Afghanistan can — and likely will — pursue indirect warfare. By covertly supporting TTP operations inside Pakistan, Kabul can keep Islamabad off balance without engaging in direct annexation. This could transform the frontier into a prolonged “gray-zone conflict” — neither peace nor open war, but an endless cycle of ambushes, drone strikes, and ceasefires.

Possible Futures: From Escalation to Containment

-

Prolonged Low-Intensity War:

The most probable outcome is a drawn-out, low-level conflict that simmers for months or years, punctuated by airstrikes and retaliatory raids. Both sides may tolerate this as a form of strategic signaling without committing to all-out war. -

Negotiated Settlement Under Chinese Mediation:

Beijing, leveraging its economic clout, could broker a border demilitarization framework tied to CPEC security guarantees. This would mirror its quiet diplomacy between Saudi Arabia and Iran in 2023. -

Internal Fracture in Pakistan:

Should Islamabad overextend militarily or fail to curb domestic terrorism, internal unrest could grow. The TTP might exploit nationalist sentiments to destabilize the state further. -

Regional Peace Initiative:

A multilateral effort involving the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) or the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) could emerge, focusing on border security, anti-terrorism coordination, and trade normalization.

Conclusion: A Fragile Truce on a Shifting Frontier

The Pakistan–Afghanistan clashes of 2025 expose a paradox at the heart of South Asia’s security architecture: the Taliban’s Afghanistan is militarily weak but ideologically resilient, while Pakistan is militarily strong but politically brittle. Each sees the other as both a threat and a mirror.

Unless the two states address their intertwined crises — TTP terrorism, border legitimacy, and economic dependency — the Durand Line will remain not a boundary, but a battlefield.

The current ceasefire may last 48 hours or 48 days, but peace will remain elusive until both sides stop fighting their past and start negotiating their future.

2025 के पाकिस्तान–अफ़ग़ानिस्तान सीमा संघर्ष: आधुनिक सीमा युद्ध की रचना

परिचय: डूरंड रेखा फिर भड़की

अक्टूबर 2025 की शुरुआत में पाकिस्तान और अफ़ग़ानिस्तान के बीच लंबे समय से simmer हो रहे तनाव ने खुली जंग का रूप ले लिया — यह संघर्ष 2021 में तालिबान के काबुल पर कब्ज़े के बाद से सबसे गंभीर टकराव बन गया है। जो अभियान पाकिस्तान ने तहरीक-ए-तालिबान पाकिस्तान (TTP) के खिलाफ शुरू किया था, वह जल्द ही एक अस्थिर सीमा युद्ध में बदल गया, जिसमें कुनर, कुर्रम, चमन–स्पिन बोलदाक और खैबर जैसे क्षेत्र जल उठे।

चिंगारी वही पुरानी थी: पाकिस्तान का आरोप कि अफ़ग़ानिस्तान TTP के आतंकियों को शरण दे रहा है, जबकि काबुल ने पलटकर कहा कि पाकिस्तान की हवाई हमले उसकी संप्रभुता का उल्लंघन हैं। कुछ ही दिनों में, दोनों तरफ़ से तोपख़ाने, ड्रोन और ज़मीनी बलों की गोलाबारी शुरू हो गई। 15 अक्टूबर तक दोनों देशों ने 48 घंटे के अस्थायी संघर्षविराम पर सहमति जताई, लेकिन यह शांति बेहद नाजुक है और जड़ में छिपे विवाद अब भी सुलझे नहीं हैं।

ऐतिहासिक पृष्ठभूमि: डूरंड रेखा का भूत

1,640 मील लंबी डूरंड रेखा, जिसे 1893 में ब्रिटिश औपनिवेशिक अधिकारियों ने खींचा था, आज भी दुनिया की सबसे विवादित सीमाओं में से एक है। अफ़ग़ानिस्तान ने इसे कभी आधिकारिक रूप से स्वीकार नहीं किया, यह तर्क देते हुए कि यह रेखा पश्तून समुदाय को दो देशों में बाँट देती है। दशकों से यही सीमा सीमा-पार आतंकवाद, क्षेत्रीय राष्ट्रवाद और छद्म युद्धों का स्रोत रही है।

पाकिस्तान ने लंबे समय तक तालिबान को भारत-विरोधी रणनीतिक बफर के रूप में देखा, लेकिन 2021 के बाद वह रणनीति उलटी पड़ गई। तालिबान से वैचारिक रूप से जुड़े लेकिन इस्लामाबाद-विरोधी TTP ने 2025 में पाकिस्तान के उत्तर-पश्चिम में सैकड़ों सैनिकों और नागरिकों की हत्या की है। यह स्थिति एक कटु विडंबना है: पाकिस्तान अब उन्हीं ताकतों से लड़ रहा है जिन्हें उसने कभी बनाया था।

अक्टूबर 2025 का समयक्रम

2–3 अक्टूबर — प्रारंभिक झड़पें (कुनर और नूरिस्तान):

कुनर के नारी ज़िले में गोलीबारी भड़की, जो नूरिस्तान और पाकिस्तान के चितरल तक फैल गई। पाकिस्तान ने अफ़ग़ानिस्तान पर TTP आतंकियों को शरण देने का आरोप लगाया; काबुल ने पलटवार में कहा कि पाकिस्तान ने बिना चेतावनी के हवाई हमले किए। कम से कम तीन पाकिस्तानी सैनिक मारे गए।

9–12 अक्टूबर — पाकिस्तान के हवाई हमले और अफ़ग़ान पलटवार:

9 अक्टूबर को पाकिस्तान ने काबुल, खोस्त और पक्तिका में कथित TTP ठिकानों पर हवाई हमले किए। नागरिक हताहतों के चलते वैश्विक निंदा हुई। तालिबान ने ज़मीन पर पलटवार किया — चमन और कुर्रम इलाकों में भारी झड़पें हुईं, जिनमें कई पाकिस्तानी चौकियां कब्ज़े में ले ली गईं। रातभर गोलियों और रॉकेटों की बरसात होती रही।

14–15 अक्टूबर — बढ़ता तनाव और अस्थायी युद्धविराम:

खैबर और ज़ज़ई मैदान में नई झड़पें हुईं; काबुल के ऊपर पाकिस्तानी ड्रोन देखे गए। कम से कम 15 अफ़ग़ान नागरिक मारे गए। पाकिस्तानी टैंक अफ़ग़ान सीमा के भीतर कई मील तक घुस आए। दोपहर तक दोनों पक्षों ने 48 घंटे के संघर्षविराम की घोषणा की, हर कोई यह दावा करता हुआ कि दूसरे ने पहले गुज़ारिश की थी।

संघर्षविराम के बावजूद छिटपुट गोलीबारी जारी रही, जो दर्शाता है कि दोनों सरकारें अपने अग्रिम मोर्चे पर पूर्ण नियंत्रण में नहीं हैं।

असमान युद्ध: हवा बनाम ज़मीन

इस संघर्ष ने सैन्य क्षमता की गहरी असमानता उजागर की है।

पाकिस्तान की बढ़त:

पाकिस्तान के पास मुस्लिम दुनिया की सबसे सक्षम वायु सेनाओं में से एक है। उसने F-16 लड़ाकू विमानों और ड्रोन के ज़रिए अफ़ग़ानिस्तान की गहराई तक हमले किए हैं। इस्लामाबाद इन हमलों को “रक्षात्मक” बताता है, जबकि काबुल और संयुक्त राष्ट्र इन्हें नागरिक हत्याओं और अंतरराष्ट्रीय कानून के उल्लंघन के रूप में देख रहे हैं।

अफ़ग़ानिस्तान की रणनीति:

तालिबान सरकार के पास प्रभावी वायुसेना नहीं है, इसलिए वह गुरिल्ला रणनीति अपनाती है — घात लगाकर हमले, पहाड़ी युद्ध और IEDs का प्रयोग। उनके लड़ाके दशकों तक NATO सेनाओं से लड़ चुके हैं, जिससे उन्हें भौगोलिक और मानसिक बढ़त मिली है। वे इस संघर्ष को राष्ट्रीय संप्रभुता और पश्तून स्वाभिमान की लड़ाई मानते हैं।

कठिन भूभाग में तालिबान की विकेन्द्रित कमान और लचीली रणनीति ने कभी-कभी पाकिस्तानी बख़्तरबंद बलों को मात दी है। कई रिपोर्टों में बताया गया है कि तालिबान ने आपूर्ति काफ़िलों पर घात लगाई, चौकियाँ कब्ज़े में लीं और पाकिस्तानी सैनिकों को पीछे हटने पर मजबूर किया।

पाकिस्तानी सैनिकों की वापसी की रिपोर्टें

कई स्वतंत्र पत्रकारों और OSINT विश्लेषकों ने पाकिस्तानी सैनिकों के पीछे हटने के प्रमाण साझा किए हैं।

-

11–12 अक्टूबर: कुर्रम और चमन सेक्टरों में तालिबान के हमलों से कई पाकिस्तानी चौकियाँ गिर गईं। सोशल मीडिया पर जारी वीडियो में तालिबान लड़ाके कब्ज़ाई चौकियों पर झंडे फहराते और जश्न मनाते दिखे।

-

कुनर सेक्टर: अफ़ग़ान बलों ने पाकिस्तानी और TTP सैनिकों को पहाड़ी ठिकानों से पीछे हटाया।

-

मानसिक प्रभाव: तालिबान — जो कभी पाकिस्तान के "रणनीतिक संपत्ति" थे — से लड़ना पाकिस्तानी सैनिकों के मनोबल पर भारी पड़ा है।

इस्लामाबाद ने इन दावों को “अतिरंजित” बताते हुए कहा कि उसने ज़मीन वापस हासिल कर ली है और “दर्जनों तालिबान” को मारा है, हालांकि स्वतंत्र सत्यापन संभव नहीं है।

क्षेत्रीय भू-राजनीति: बदलता शतरंज बोर्ड

-

चीन की दुविधा:

पाकिस्तान का सबसे बड़ा साझेदार चीन इस संघर्ष से चिंतित है क्योंकि यह चीन-पाकिस्तान आर्थिक गलियारा (CPEC) की सुरक्षा को खतरे में डाल सकता है। बीजिंग ने दोनों से संयम बरतने का आग्रह किया है। -

भारत की रणनीति:

पाकिस्तान ने भारत पर अफ़ग़ानिस्तान को समर्थन देने का आरोप लगाया है — हालांकि भारत ने इससे इनकार किया। फिर भी भारतीय विश्लेषकों का मानना है कि यह संघर्ष पाकिस्तान की पश्चिमी सीमा को कमजोर करता है, जिससे कश्मीर में दबाव घट सकता है। -

खाड़ी देश और अमेरिका:

क़तर और सऊदी अरब ने मध्यस्थता की पेशकश की है। अमेरिका ने संयम बरतने की अपील की है, लेकिन किसी पक्ष का समर्थन नहीं किया — पाकिस्तान के परमाणु हथियार और अफ़ग़ानिस्तान की अलगाव की स्थिति इसे एक जटिल संतुलन बनाते हैं। -

ईरान और रूस:

दोनों देशों ने इसे “अमेरिकी विफलता” का प्रमाण बताया है। ईरान ने अपनी सीमा पर निगरानी बढ़ा दी है और "अफ़ग़ान-नेतृत्व वाले संवाद" की वकालत की है।

क्या तालिबान खैबर पख्तूनख्वा पर कब्ज़ा कर सकता है?

यह प्रश्न सोशल मीडिया पर तेजी से फैल रहा है — क्या तालिबान पाकिस्तान के पश्तून-बहुल क्षेत्रों पर नियंत्रण कर सकता है?

भावनात्मक रूप से यह आकर्षक लग सकता है, परंतु वास्तविकता में असंभव है। अफ़ग़ानिस्तान की अर्थव्यवस्था ध्वस्त है, वायुसेना लगभग शून्य है और भारी हथियार सीमित हैं। पाकिस्तान, इसके विपरीत, दुनिया की सबसे शक्तिशाली सेनाओं में से एक रखता है और परमाणु शक्ति है। किसी भी आक्रामक कदम का परिणाम विनाशकारी प्रतिशोध होगा।

हाँ, अफ़ग़ानिस्तान अप्रत्यक्ष युद्ध का रास्ता ज़रूर अपना सकता है — TTP को समर्थन देकर पाकिस्तान के अंदर अस्थिरता बढ़ाना। यह सीमा को “धूसर क्षेत्रीय संघर्ष” (gray-zone conflict) में बदल देगा — जहाँ न युद्ध समाप्त होता है, न शांति टिकती है।

संभावित भविष्य परिदृश्य

-

दीर्घकालिक कम-तीव्रता वाला युद्ध:

सबसे संभावित परिदृश्य यही है — महीनों या वर्षों तक छिटपुट झड़पें, हवाई हमले और प्रतिशोधी कार्रवाइयाँ। दोनों पक्ष इसे "नियंत्रित संघर्ष" के रूप में स्वीकार कर सकते हैं। -

चीनी मध्यस्थता के तहत वार्ता:

बीजिंग आर्थिक दबाव का उपयोग कर सीमा-विराम समझौता करा सकता है, जैसा उसने 2023 में सऊदी-अरब और ईरान के बीच किया था। -

पाकिस्तान के भीतर अस्थिरता:

यदि इस्लामाबाद ने अत्यधिक सैन्य दबाव झेला या TTP हमले बढ़े, तो आंतरिक विद्रोह की संभावना है। -

क्षेत्रीय शांति पहल:

OIC या SCO जैसे बहुपक्षीय मंच सीमा सुरक्षा और व्यापार पुनर्स्थापना पर काम कर सकते हैं।

निष्कर्ष: बदलती सीमा पर नाजुक शांति

2025 के पाकिस्तान–अफ़ग़ानिस्तान संघर्ष ने दक्षिण एशिया की सुरक्षा संरचना का विरोधाभास उजागर किया है — तालिबान का अफ़ग़ानिस्तान सैन्य रूप से कमजोर लेकिन वैचारिक रूप से दृढ़ है; जबकि पाकिस्तान सैन्य रूप से मजबूत लेकिन राजनीतिक रूप से अस्थिर।

जब तक दोनों देश अपने साझा संकटों — TTP आतंकवाद, सीमा की वैधता, और आर्थिक निर्भरता — का समाधान नहीं करते, डूरंड रेखा एक सीमा नहीं, बल्कि युद्धभूमि बनी रहेगी।

वर्तमान संघर्षविराम 48 घंटे या 48 दिन चल सकता है, लेकिन स्थायी शांति तब तक संभव नहीं जब तक दोनों अपने अतीत से लड़ना छोड़कर भविष्य पर बात करना नहीं सीखते।

The Durand Line: A Border Drawn in Empire, Disputed in Eternity

Introduction: A Line That Divides and Defines

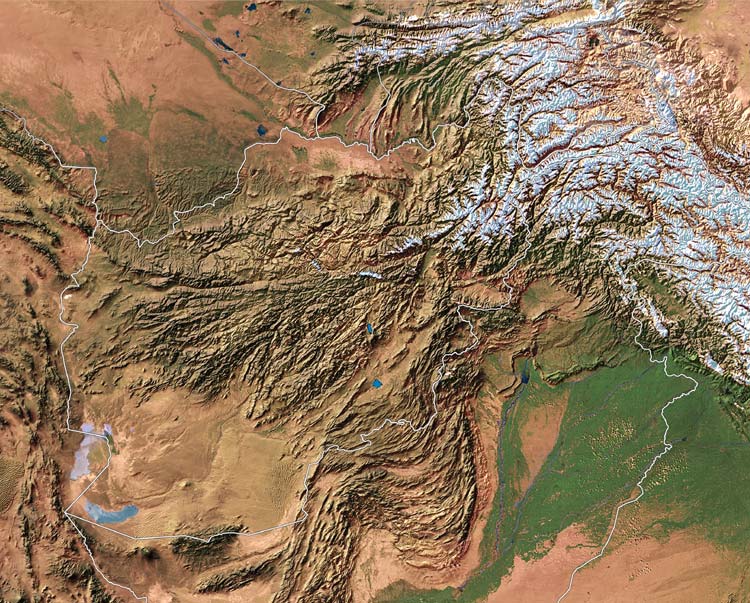

The Durand Line — a 2,640-kilometer (1,640-mile) frontier stretching from the Iranian border in the west to China in the east — is not just a line on a map. It is one of the world’s most controversial and militarized borders, a colonial relic that continues to shape geopolitics, identity, and conflict in South and Central Asia.

Carved through mountain ranges like the Hindu Kush, Spīn Ghar, and Karakoram, and across deserts such as the Registan, it divides ethnic Pashtun and Baloch communities whose families, tribes, and trade networks predate the modern nation-state. Major crossings — Torkham (via the Khyber Pass) and Chaman–Spin Boldak — serve as critical trade arteries but are also flashpoints for smuggling, insurgency, and political tension.

Scholars and security experts alike describe it as “one of the world’s most dangerous borders” — a frontier of narcotics trafficking, militant infiltration, and competing sovereignties.

Origins in the Great Game (19th Century)

The Durand Line was born amid the “Great Game,” the 19th-century imperial contest between the British Empire and Tsarist Russia for control of Central Asia. Afghanistan stood between them — a buffer state that both powers sought to influence but not occupy outright.

After the Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878–1880), the Treaty of Gandamak ceded several frontier districts to British India, setting the stage for a formal demarcation.

On November 12, 1893, British diplomat Sir Mortimer Durand met Emir Abdur Rahman Khan in Kabul to sign the Durand Line Agreement — a terse, seven-article document written on a single page. The agreement defined “spheres of influence” between the two states, recognizing Afghan independence in domestic matters but granting Britain control of foreign policy and external relations.

Key provisions included:

-

Non-interference beyond the border,

-

Territorial exchanges (Afghanistan gained Asmar and parts of Kunar, but lost Waziristan and Chageh),

-

Permission for Afghan arms imports via British India, and

-

An increased annual subsidy from 1.2 million to 1.8 million rupees.

Between 1894 and 1896, British and Afghan surveyors marked roughly 800 miles of the frontier — producing detailed topographical maps that remain reference points today.

Yet from the Afghan perspective, the treaty was signed under duress. Abdur Rahman Khan, facing both British pressure and internal rebellion, viewed it as a temporary arrangement, not a permanent surrender of territory. Britain, by contrast, saw it as an enduring border necessary for imperial security.

Early 20th Century Reaffirmations

Resistance to the new border was fierce. Tribal uprisings — especially among the Afridis and Wazirs — erupted soon after. Britain responded by extending railways and fortifications through the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP), established in 1901 to consolidate its control.

The Third Anglo-Afghan War (1919) culminated in the Treaty of Rawalpindi, whose Article V reaffirmed the Durand Line as the Indo-Afghan frontier. This was followed by the Treaty of Kabul (1921), signed by Mahmud Tarzi and Sir Henry Dobbs, which fine-tuned the demarcation around the Khyber Pass. Minor border adjustments continued into the 1930s.

By the eve of World War II, the Durand Line had acquired de facto international recognition — though resentment lingered across Afghan society.

Partition and Post-1947 Disputes

When British India was partitioned in 1947, Pakistan inherited the Durand Line under the international law principle of uti possidetis juris — that new states retain the administrative boundaries of their colonial predecessors. Britain, the United Nations, and later the U.S. State Department (2004) reaffirmed this.

Afghanistan, however, rejected the transfer outright. In 1949, a Loya Jirga declared the Durand Agreement void, citing coercion and British manipulation. This followed a Pakistani airstrike on the Afghan village of Mogalghai, which inflamed public outrage.

From then onward, no Afghan government — monarchical, republican, communist, or Taliban — has recognized the border.

Meanwhile, Pashtun nationalism surged. Leaders like Abdul Ghaffar Khan (Bacha Khan), though initially advocating for a united India or Pashtun autonomy, became symbols of the trans-border struggle. Kabul began championing the idea of “Pashtunistan” — a sovereign state for Pashtuns extending up to the Indus River.

In 1976, Afghan President Daoud Khan and Pakistani Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto nearly reached an understanding, but both were overthrown in coups the following years — Daoud in 1978, Bhutto in 1977 — derailing progress.

Cold War and Taliban Era

The Soviet-Afghan War (1979–1989) transformed the Durand Line into a militarized corridor. Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), with CIA backing, funneled weapons and money to the Mujahideen through porous crossings, while Afghan intelligence retaliated with bombings and cross-border infiltration.

After the Soviet withdrawal (1989) and Taliban emergence (1994), Pakistan sought “strategic depth” in Afghanistan — but by 2001, Taliban leaders rejected colonial borders altogether, calling for unity among Muslims “beyond artificial lines.”

The post-9/11 U.S.-led intervention revived old tensions. While Pakistan aligned with Washington, Afghanistan accused Islamabad of harboring Taliban remnants. Border skirmishes became frequent, particularly around Torkham and Spin Boldak.

Contemporary Controversy

The Durand Line’s enduring volatility stems from more than geopolitics — it is a civilizational fault line.

Afghan Perspective:

Kabul insists the Durand Line is “a line of hatred,” imposed under duress. Every Afghan leader since 1947 — from Daoud Khan to Hamid Karzai to the current Taliban regime — has rejected it. Afghan schoolchildren are often taught maps that omit the line entirely, symbolizing a collective refusal to accept its legitimacy. Fencing projects by Pakistan are viewed as violations of sovereignty and deliberate attempts to divide the Pashtun nation.

Pakistani Perspective:

Islamabad, by contrast, sees the border as legally binding and immutable under international law. It argues there is no “expiry clause” and cites multiple treaties, including the Vienna Convention, to support its stance. Pakistan’s fencing of the frontier — completed by 2023 (2,611 km) at a cost exceeding $530 million — is portrayed as essential for national security, curbing TTP militancy, narcotics, and smuggling.

International Position:

Major powers, including the U.K., U.S., and regional organizations like SEATO, have consistently upheld Pakistan’s sovereignty up to the Durand Line. The UN has not recognized Afghan claims, viewing them as political rather than legal.

Recent Developments (as of October 2025)

The border remains volatile.

-

2003: Skirmishes erupted in Yaqubi.

-

2007–2011: Clashes over fencing and artillery exchanges killed dozens.

-

2017: Prolonged closures cost Afghanistan $90 million in trade losses.

-

2021: The Taliban captured Spin Boldak, seizing control of one of the busiest trade routes.

-

2023: Pakistan announced completion of 98% of border fortifications.

-

October 2025: Full-scale fighting erupted, prompting a 48-hour ceasefire after Pakistan’s airstrikes and Taliban retaliation — underscoring how the Durand Line remains a live flashpoint.

Afghanistan continues to refuse recognition, while Pakistan enforces strict control through checkpoints and surveillance towers. On social media platform X (formerly Twitter), Afghan users deride the fence as “the scar of empire,” while Pakistanis defend it as “the shield of sovereignty.”

Analysis: The Line That Refuses to Fade

The Durand Line is not just a geopolitical boundary — it is a psychological and cultural wound. It separates tribes from tribes, markets from markets, and identities from nations. Yet, for all its controversy, it remains the de facto border under international law.

In an era of global interconnectedness, the dispute underscores how 19th-century colonial cartography still shapes 21st-century conflict. Without bilateral dialogue and mutual recognition, the Durand Line will continue to serve as both a wall of division and a bridge of insurgency.

For Pakistan, enforcing it is a matter of security.

For Afghanistan, rejecting it is a matter of sovereignty.

For the Pashtuns, it is a question of belonging.

And for the world — it remains a reminder that some borders, once drawn, never truly stop bleeding.

डूरंड रेखा: एक साम्राज्य द्वारा खींची गई रेखा, जो आज भी विवादों में ज़िंदा है

परिचय: एक रेखा जो बाँटती भी है और परिभाषित भी करती है

डूरंड रेखा — 2,640 किलोमीटर (1,640 मील) लंबी यह सीमा रेखा पश्चिम में ईरान से लेकर पूर्व में चीन तक फैली है। यह केवल नक्शे पर खींची गई एक रेखा नहीं है, बल्कि दुनिया की सबसे विवादास्पद और सैन्य रूप से संवेदनशील सीमाओं में से एक है — एक उपनिवेशकालीन विरासत जो आज भी दक्षिण और मध्य एशिया की राजनीति, पहचान और संघर्ष को आकार दे रही है।

यह रेखा हिंदू कुश, स्पिन घर (सफेद पर्वत) और काराकोरम जैसी पर्वत श्रृंखलाओं को पार करती है, और रेगिस्तान रेजिस्तान जैसे सूखे क्षेत्रों से होकर गुजरती है। यह पश्तून और बलोच समुदायों को विभाजित करती है, जिनकी पारिवारिक और व्यापारिक जड़ें आधुनिक राष्ट्र-राज्यों से भी पहले की हैं।

मुख्य पारगमन बिंदु — खैबर दर्रे के रास्ते तोर्खम और चमन–स्पिन बोलदक — व्यापार के लिए महत्वपूर्ण हैं, परंतु इन्हीं क्षेत्रों में तस्करी, उग्रवाद और अवैध आवाजाही सबसे अधिक होती है।

सुरक्षा विशेषज्ञ इसे अक्सर “दुनिया की सबसे खतरनाक सीमाओं में से एक” कहते हैं — एक ऐसी रेखा जहाँ हथियार, नशा और विद्रोह लगातार पार होते रहते हैं।

उत्पत्ति: "ग्रेट गेम" और ब्रिटिश रणनीति (19वीं सदी)

डूरंड रेखा का जन्म 19वीं सदी के “ग्रेट गेम” के दौरान हुआ — जब ब्रिटिश साम्राज्य और जारवादी रूस मध्य एशिया में प्रभाव के लिए प्रतिस्पर्धा कर रहे थे। अफ़ग़ानिस्तान उस समय दोनों के बीच एक बफर राज्य था, जिसे कोई भी खुलकर कब्ज़ा नहीं करना चाहता था।

दूसरे एंग्लो-अफ़ग़ान युद्ध (1878–1880) के बाद हुए गंडामक संधि (1880) के तहत अफ़ग़ानिस्तान ने अपने कई सीमावर्ती क्षेत्र ब्रिटिश भारत को सौंप दिए। यही आगे चलकर डूरंड समझौते की नींव बनी।

12 नवम्बर 1893 को ब्रिटिश राजनयिक सर मॉर्टिमर डूरंड और अफ़ग़ान शासक अमीर अब्दुर रहमान खान ने काबुल में डूरंड रेखा समझौते पर हस्ताक्षर किए। सात अनुच्छेदों वाला यह एक-पृष्ठीय समझौता ब्रिटिश और अफ़ग़ान "प्रभाव क्षेत्रों" को परिभाषित करता था।

मुख्य बिंदु इस प्रकार थे:

-

सीमा पार किसी भी हस्तक्षेप पर रोक,

-

कुछ क्षेत्रों का आदान-प्रदान (अफ़ग़ानिस्तान को असमर और कुनर का हिस्सा मिला, पर उसने वज़ीरिस्तान और चाघी छोड़ दिए),

-

ब्रिटिश भारत से हथियार आयात की अनुमति,

-

और अफ़ग़ानिस्तान की वार्षिक सब्सिडी 12 लाख से बढ़ाकर 18 लाख रुपये कर दी गई।

1894–1896 के बीच ब्रिटिश और अफ़ग़ान सर्वेयरों ने लगभग 800 मील की सीमा रेखा तय की। लेकिन अफ़ग़ान दृष्टिकोण से यह संधि दबाव में साइन की गई थी। अब्दुर रहमान खान ने इसे एक स्थायी सीमा नहीं, बल्कि अस्थायी “प्रभाव क्षेत्र” के रूप में देखा, जबकि ब्रिटिश इसे अपने साम्राज्य की सुरक्षा के लिए आवश्यक स्थायी सीमा मानते थे।

20वीं सदी की शुरुआत: पुनर्पुष्टि और विरोध

रेखा खिंचने के तुरंत बाद ही अफ़रीदी और वज़ीरी जनजातियों ने इसका विरोध शुरू कर दिया। ब्रिटिशों ने इसका जवाब उत्तर-पश्चिम सीमांत प्रांत (NWFP) की स्थापना (1901) से दिया, जहाँ उन्होंने रेलमार्ग और किलों का विस्तार किया।

तीसरा एंग्लो-अफ़ग़ान युद्ध (1919) समाप्त हुआ रावलपिंडी संधि से, जिसके अनुच्छेद V में डूरंड रेखा को औपचारिक रूप से भारत–अफ़ग़ान सीमा के रूप में मान्यता दी गई। इसके बाद 1921 की काबुल संधि, जिसे महमूद तरज़ी और सर हेनरी डॉब्स ने हस्ताक्षरित किया, ने खैबर दर्रे के आसपास की सीमाओं को और स्पष्ट किया।

1930 के दशक तक यह रेखा अंतरराष्ट्रीय स्तर पर स्वीकार की जा चुकी थी — हालांकि अफ़ग़ान समाज में असंतोष बना रहा।

1947 के बाद: विभाजन और अस्वीकृति

1947 में भारत के विभाजन के साथ ही पाकिस्तान ने डूरंड रेखा को अंतरराष्ट्रीय क़ानून के तहत उत्तराधिकारी सीमा (uti possidetis juris) के रूप में विरासत में पाया। ब्रिटेन, संयुक्त राष्ट्र, और बाद में अमेरिकी विदेश मंत्रालय (2004) ने भी इसे मान्यता दी।

लेकिन 1949 में अफ़ग़ानिस्तान की लोया जिरगा ने इस समझौते को “काल्पनिक और अमान्य” घोषित कर दिया। यह घोषणा एक पाकिस्तानी हवाई हमले के बाद हुई थी, जिसने एक अफ़ग़ान गाँव को निशाना बनाया था।

उसके बाद से अब तक — किसी भी अफ़ग़ान सरकार ने (चाहे राजशाही, गणराज्य, कम्युनिस्ट या तालिबान) — इस रेखा को औपचारिक रूप से स्वीकार नहीं किया है।

इसी दौरान पश्तून राष्ट्रवाद उभरा। अब्दुल ग़फ़्फ़ार ख़ान (बाचा ख़ान) जैसे नेताओं ने पहले “संयुक्त भारत” की वकालत की, फिर “पश्तूनिस्तान” की — जो सिंधु नदी तक फैला एक स्वतंत्र राज्य हो।

1976 में अफ़ग़ान राष्ट्रपति दाऊद ख़ान और पाकिस्तानी प्रधानमंत्री ज़ुल्फ़िकार अली भुट्टो के बीच लगभग समझौता हो ही गया था, लेकिन अगले ही वर्षों में दोनों की सत्ता पलट गई — और शांति का अवसर समाप्त हो गया।

शीतयुद्ध और तालिबान युग

1979–1989 के सोवियत–अफ़ग़ान युद्ध ने डूरंड रेखा को एक युद्धक्षेत्र में बदल दिया। पाकिस्तान की आईएसआई ने अमेरिकी सीआईए के साथ मिलकर हथियार और धन अफ़ग़ान मुजाहिदीन को भेजे। इसके जवाब में अफ़ग़ान खुफिया एजेंसियों ने पाकिस्तान में बम धमाके और घुसपैठ शुरू की।

1990 के दशक में तालिबान का उदय हुआ। पाकिस्तान ने अफ़ग़ानिस्तान में “रणनीतिक गहराई” (strategic depth) बनाने की कोशिश की, लेकिन 2001 तक तालिबान नेताओं ने धार्मिक आधार पर कहा कि “मुसलमानों के बीच कोई सीमा नहीं होती।”

9/11 के बाद अमेरिका के नेतृत्व में हुए आक्रमण ने स्थिति को और जटिल बना दिया — पाकिस्तान ने अमेरिका का साथ दिया, जबकि अफ़ग़ानिस्तान ने पाकिस्तान पर तालिबान को पनाह देने का आरोप लगाया। सीमा संघर्ष लगातार बढ़ते गए।

आधुनिक विवाद

डूरंड रेखा का विवाद केवल राजनीति का नहीं, बल्कि सभ्यतागत पहचान का सवाल बन गया है।

अफ़ग़ान दृष्टिकोण:

काबुल इस रेखा को “घृणा की रेखा” कहता है — दबाव में हस्ताक्षरित एक औपनिवेशिक थोपन। 1947 के बाद से लेकर आज के तालिबान शासन तक, किसी भी अफ़ग़ान नेता ने इसे मान्यता नहीं दी। अफ़ग़ान बच्चों को पढ़ाए जाने वाले नक्शों में यह रेखा अक्सर अनुपस्थित रहती है। पाकिस्तान द्वारा सीमा पर की गई फेंसिंग (दीवारबंदी) को “राष्ट्रीय विभाजन” के प्रतीक के रूप में देखा जाता है।

पाकिस्तानी दृष्टिकोण:

इस्लामाबाद इसे एक क़ानूनी और स्थायी अंतरराष्ट्रीय सीमा मानता है, जिसकी कोई समयसीमा नहीं है। पाकिस्तान वियना कन्वेंशन जैसे अंतरराष्ट्रीय क़ानूनों का हवाला देता है और कहता है कि अफ़ग़ान अस्वीकृति एकतरफ़ा है।

2017 से शुरू हुई सीमा फेंसिंग 2023 तक 98% (2,611 किमी) पूरी हो चुकी है, जिस पर $530 मिलियन से अधिक खर्च आया। पाकिस्तान के अनुसार यह आतंकवाद, टीटीपी, तस्करी और अवैध घुसपैठ को रोकने के लिए आवश्यक कदम है।

अंतरराष्ट्रीय दृष्टिकोण:

ब्रिटेन, अमेरिका, SEATO जैसी संस्थाओं ने लगातार पाकिस्तान की सीमा-संप्रभुता को स्वीकार किया है। संयुक्त राष्ट्र ने भी अफ़ग़ान दावों को “राजनीतिक” मानकर किसी पक्ष का समर्थन नहीं किया।

हाल की स्थिति (अक्टूबर 2025 तक)

सीमा अब भी अस्थिर है:

-

2003: याक़ूबी में झड़पें

-

2007–2011: फेंसिंग को लेकर गोलीबारी

-

2017: सीमा बंदी से अफ़ग़ानिस्तान को $90 मिलियन का व्यापारिक नुकसान

-

2021: तालिबान ने स्पिन बोलदक पारगमन बिंदु कब्ज़ा किया

-

2023: पाकिस्तान ने 338 चौकियों के साथ फेंसिंग पूरी करने की घोषणा की

-

अक्टूबर 2025: सीमा पर पूर्ण संघर्ष, पाकिस्तान के हवाई हमले और तालिबान की जवाबी कार्रवाई के बाद 48 घंटे का युद्धविराम

ऑनलाइन प्लेटफ़ॉर्म X (पूर्व में ट्विटर) पर अफ़ग़ान उपयोगकर्ता इस दीवार को “औपनिवेशिक ज़ख्म” कहते हैं, जबकि पाकिस्तानी इसे “संप्रभुता की ढाल” बताते हैं।

विश्लेषण: एक रेखा जो मिटने से इंकार करती है

डूरंड रेखा केवल एक भौगोलिक सीमा नहीं — यह एक सांस्कृतिक और मनोवैज्ञानिक विभाजन है। यह जनजातियों को अलग करती है, बाजारों को बाँटती है, और पहचान को दो हिस्सों में काटती है।

फिर भी, अंतरराष्ट्रीय क़ानून के तहत यह अब भी de facto सीमा है।

यह विवाद दिखाता है कि 19वीं सदी के औपनिवेशिक नक्शे आज भी 21वीं सदी के संघर्ष तय कर रहे हैं।

जब तक पाकिस्तान और अफ़ग़ानिस्तान आपसी बातचीत और मान्यता के रास्ते पर नहीं आते, यह रेखा दीवार भी बनी रहेगी और युद्ध का पुल भी।

पाकिस्तान के लिए यह सुरक्षा का प्रश्न है।

अफ़ग़ानिस्तान के लिए यह संप्रभुता का प्रश्न है।

और पश्तूनों के लिए — यह अस्तित्व और पहचान का प्रश्न है।

और दुनिया के लिए, यह एक याद दिलाने वाली रेखा है —

कि कुछ सीमाएँ एक बार खींच दी जाएँ, तो सदियों तक खून बहाती रहती हैं।

When Empires Drew Lines: The Borders That Still Bleed

Introduction: The Arrogance of the Colonial Mapmaker

The European colonialists didn’t just conquer land — they redesigned the world with rulers and pens. In their pursuit of power and profit, they redrew entire civilizations into arbitrary territories, dissecting cultures, languages, and communities that had coexisted for centuries.

The British Empire, in particular, perfected this art of division. They called it “administration,” but history remembers it as cartographic violence — a process by which millions were uprooted, countless lives were lost, and new nations were born with scars that never truly healed.

The Partition That Tore a Subcontinent Apart

Nowhere was this arrogance more catastrophic than in the Partition of India in 1947. In just a few weeks, British bureaucrats divided one of the most diverse civilizations on earth — Punjab and Bengal — with chilling efficiency and zero empathy.

A man named Cyril Radcliffe, who had never set foot in India before, was asked to draw the borders of two new nations. Working from outdated maps and incomplete census data, he drew the Radcliffe Line that sliced through villages, rivers, and farmlands — and through the hearts of millions.

The result was one of the largest and bloodiest forced migrations in human history. Over a million people died, and more than 15 million were displaced. Families were split, trains arrived full of corpses, and neighbors who once shared festivals turned into enemies overnight.

The British left — and South Asia was left to pick up the pieces of their geometry.

Before Partition: The Forgotten Division of Mithila

Long before Punjab and Bengal were split, another cultural region was quietly dissected — Mithila, the ancient land of King Janak and Goddess Sita. Once a unified civilizational zone stretching from northern Bihar to eastern Nepal, it was divided by the British colonial and later international borders that followed no cultural or linguistic logic.

This artificial line cut through a shared heritage of language, art, and philosophy — from the Maithili-speaking plains of Darbhanga and Madhubani to the Terai of Janakpur. Even today, the people on both sides share the same festivals, food, and folklore, but they live under different flags, passports, and governments.

The division of Mithila is a quieter tragedy — one that didn’t make global headlines, but continues to erode identity, economy, and unity in subtle ways.

The Line That Still Burns: The India–China Border

The chaos didn’t end in 1947. It extended into the high Himalayas, where the British-drawn maps of the 19th century created another ghost — the India–China border. The infamous McMahon Line, drafted during the 1914 Simla Convention, was the product of similar arrogance: outsiders deciding the fate of mountain peoples without ever walking those mountains.

Today, that line remains one of the world’s most dangerous flashpoints — the site of deadly clashes, nationalism, and diplomatic stalemates. Soldiers die each year defending ridges that a British official once drew in ink, never imagining that his line would one day become a frontier between two nuclear powers.

Africa: The Continent of Broken Lines

If South Asia’s story is tragic, Africa’s is even worse. European powers, led by Britain, France, and Belgium, sat around a table in Berlin in 1884, during what is now called the Berlin Conference, and divided the entire continent like slices of cake — without a single African voice in the room.

They drew borders that ignored rivers, tribes, languages, and ancient kingdoms. Entire ethnic groups were split between colonies; enemies were forced into the same artificial states.

The consequences still reverberate: from Nigeria’s Biafra war to Rwanda’s genocide, from Sudan’s civil wars to the ongoing instability across the Sahel. Each of these tragedies is, in part, a consequence of lines drawn in European dining halls by men who saw maps as games and people as pawns.

Cartographic Colonialism: The World as a British Drawing Room

Colonial mapmaking was not science — it was control disguised as geometry. The colonizers used borders as tools of dominance, deliberately splitting unified societies to prevent collective resistance. They called it “divide and rule.”

But what they truly did was divide and ruin.

Across Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, entire generations have paid for those decisions. From Palestine’s contested map to Kashmir’s frozen conflict, from Sudan’s endless partitioning to the Kurdish question — the legacy of European cartography continues to redraw the world in blood.

Conclusion: The Lines Must Heal

Borders today are not just lines on maps — they are open wounds. The colonialists may be gone, but the chaos they left behind still defines global politics, migration, and identity.

It is time for the world to acknowledge that these boundaries were not born of culture or consent — they were born of greed and ignorance. The first step toward peace in many regions is to understand the injustice of how those lines were drawn.

Perhaps, one day, humanity will stop worshipping the lines of empire — and start erasing them with the ink of cooperation, dignity, and shared destiny.

Because until we do, the world will remain what the colonizers made it:

a map full of borders, and a history full of pain.

जब साम्राज्यों ने रेखाएँ खींचीं: वे सीमाएँ जो आज भी लहूलुहान हैं

भूमिका: औपनिवेशिक नक़्शानवीसों का अहंकार

यूरोपीय उपनिवेशवादियों ने सिर्फ़ ज़मीनें नहीं जीतीं — उन्होंने पैमाने और कलम से पूरी दुनिया को फिर से गढ़ दिया। सत्ता और लाभ के लालच में उन्होंने सदियों से साथ रहने वाली सभ्यताओं को मनमाने तरीक़े से बाँट दिया, भाषाओं, संस्कृतियों और परिवारों को तोड़ दिया।

ब्रिटिश साम्राज्य ने इस “विभाजन की कला” को चरम तक पहुँचाया। उन्होंने इसे “प्रशासन” कहा, लेकिन इतिहास इसे मानचित्रिक हिंसा (cartographic violence) के नाम से याद करता है — वह प्रक्रिया जिसमें लाखों लोग विस्थापित हुए, असंख्य मारे गए, और जो राष्ट्र बने वे अपनी चोटें आज तक ढो रहे हैं।

भारत का विभाजन: एक महाद्वीप की आत्मा को चीर देने वाला फैसला

इस अहंकार का सबसे बड़ा उदाहरण था 1947 में भारत का विभाजन। कुछ ही हफ्तों में ब्रिटिश अधिकारियों ने धरती की सबसे विविधतापूर्ण सभ्यता को काट दिया — पंजाब और बंगाल को मनमाने ढंग से विभाजित कर दिया।

एक व्यक्ति — सर सिरिल रैडक्लिफ़, जिसने कभी भारत की धरती पर क़दम तक नहीं रखा था, को यह काम सौंपा गया कि वह दो नए राष्ट्रों की सीमाएँ तय करे। पुराने नक्शों और अधूरे जनगणना आँकड़ों के सहारे उसने एक रेड्क्लिफ़ लाइन खींची — जो नदियों, खेतों, गाँवों और इंसानी दिलों को बीच से काट गई।

परिणाम भयावह था: मानव इतिहास के सबसे बड़े और रक्तरंजित विस्थापनों में से एक।

एक मिलियन (दस लाख) लोग मारे गए, पंद्रह मिलियन (डेढ़ करोड़) से अधिक विस्थापित हुए। परिवार बिछड़ गए, रेलगाड़ियाँ लाशों से भरकर आईं, और पड़ोसी जो कभी साथ त्योहार मनाते थे, एक-दूसरे के ख़िलाफ़ हथियार उठा बैठे।

ब्रिटिश चले गए — और दक्षिण एशिया को छोड़ गए अपने नक़्शे की रेखाओं से बने ज़ख्मों के साथ।

विभाजन से पहले: मिथिला का मौन बँटवारा

पंजाब और बंगाल से पहले भी ब्रिटिशों ने एक और सांस्कृतिक इकाई को बाँट दिया था — मिथिला।

यह वह भूमि थी जहाँ राजा जनक और देवी सीता की सभ्यता फली-फूली थी। कभी यह एक अखंड सांस्कृतिक क्षेत्र था, जो उत्तर बिहार से लेकर नेपाल के तराई क्षेत्र तक फैला हुआ था।

लेकिन ब्रिटिश औपनिवेशिक प्रशासन और बाद में बनी अंतरराष्ट्रीय सीमाओं ने इस क्षेत्र को बिना किसी सांस्कृतिक या भाषाई आधार के दो हिस्सों में बाँट दिया।

इस कृत्रिम रेखा ने साझा भाषा, परंपरा, और दर्शन की एकता को तोड़ दिया — दरभंगा और मधुबनी से लेकर जनकपुर तक फैले मैथिलीभाषी क्षेत्र अब अलग-अलग राष्ट्रों में बँट गए। आज भी दोनों ओर के लोग एक ही त्यौहार मनाते हैं, एक जैसी बोली बोलते हैं, लेकिन दो अलग-अलग पासपोर्ट रखते हैं।

मिथिला का यह बँटवारा शांत है, परंतु गहरा — एक ऐसा सांस्कृतिक घाव जो धीरे-धीरे पहचान, अर्थव्यवस्था और एकता को खोखला करता जा रहा है।

भारत–चीन सीमा: एक रेखा जो अब भी सुलग रही है

ब्रिटिशों की बनाई सीमाओं का दंश यहीं खत्म नहीं हुआ। यह हिमालय की चोटियों तक पहुँचा, जहाँ 19वीं सदी में ब्रिटिशों द्वारा खींचे गए नक्शों ने भारत–चीन सीमा का भूत पैदा किया।

1914 की शिमला संधि के दौरान खींची गई मैकमहोन रेखा भी उसी औपनिवेशिक अहंकार की उपज थी — ऐसे अफसरों का निर्णय जिन्होंने न तो कभी इन पहाड़ों को देखा था और न ही वहाँ के लोगों की संस्कृति को समझा था।

आज वही रेखा दुनिया की सबसे ख़तरनाक सीमाओं में से एक बन चुकी है — जहाँ हर साल सैनिक मरते हैं, जहाँ दो परमाणु शक्तियाँ आमने-सामने खड़ी हैं। यह सब उस स्याही का नतीजा है, जो एक ब्रिटिश अधिकारी ने कभी सहजता से कागज़ पर गिराई थी।

अफ़्रीका: टूटी सीमाओं का महाद्वीप

यदि एशिया की कहानी त्रासदी है, तो अफ़्रीका की कहानी उससे भी भयावह है।

1884 में बर्लिन सम्मेलन में यूरोपीय शक्तियाँ — ब्रिटेन, फ्रांस और बेल्जियम — डिनर टेबल पर बैठीं और पूरे महाद्वीप को क़ेक की तरह बाँट लिया।

कमरे में कोई अफ्रीकी नहीं था। उन्होंने न नदियाँ देखीं, न भाषाएँ सुनीं, न जनजातियों का इतिहास समझा। उन्होंने सिर्फ़ नक्शे पर रेखाएँ खींचीं।

परिणाम: नाइजीरिया का बियाफ्रा युद्ध, रवांडा का नरसंहार, सूडान के गृहयुद्ध, और आज भी जारी साहेल क्षेत्र की अस्थिरता — सब उन रेखाओं की विरासत हैं जो यूरोपीय भोजन टेबलों पर खींची गई थीं।

नक्शे की राजनीति: जब भूगोल बना औज़ार

औपनिवेशिक नक्शानवीसी कोई विज्ञान नहीं थी — यह नियंत्रण का औज़ार थी।

उनके लिए सीमाएँ सत्ता का साधन थीं — “फूट डालो और राज करो” केवल नीति नहीं, नक्शे की रेखाओं में ढली रणनीति थी।

पर असलियत यह थी कि उन्होंने “फूट डालो और बरबाद करो” की राजनीति की।

एशिया से लेकर अफ़्रीका और मध्य पूर्व तक, पीढ़ियाँ इस अपराध की क़ीमत चुका रही हैं। फ़िलिस्तीन के नक्शे का संकट, कश्मीर का स्थायी तनाव, सूडान का बार-बार का विभाजन, कुर्दों की अधूरी मातृभूमि — सब कहीं न कहीं औपनिवेशिक रेखाओं के ही परिणाम हैं।

निष्कर्ष: रेखाएँ मिटनी चाहिए, ज़ख्म भरने चाहिए

आज की सीमाएँ सिर्फ़ नक्शों पर बनी रेखाएँ नहीं हैं — वे खुले ज़ख्म हैं।

औपनिवेशिक शक्तियाँ भले चली गईं, लेकिन उन्होंने जो अराजकता छोड़ी, वही आज भी हमारी दुनिया की राजनीति, प्रवास, और पहचान तय करती है।

यह स्वीकार करने का समय है कि ये सीमाएँ संस्कृति या सहमति से नहीं, बल्कि लोभ और अज्ञानता से पैदा हुईं।

शांति की दिशा में पहला क़दम है — यह समझना कि ये रेखाएँ इंसानियत के नहीं, साम्राज्यवाद के दस्तख़त हैं।

शायद एक दिन, मानवता इन औपनिवेशिक रेखाओं की पूजा करना छोड़ देगी —

और उन्हें सहयोग, गरिमा और साझा भविष्य की स्याही से मिटा देगी।

क्योंकि जब तक ऐसा नहीं होता, दुनिया वैसी ही रहेगी जैसी यूरोपीय साम्राज्यों ने बनाई थी —

एक नक्शा जो सीमाओं से भरा है, और एक इतिहास जो दर्द से भरा है।

The Way Out: Why Peace, Not Borders, Defines the Future

Introduction: The Age of Artificial Borders

The 20th century was defined by the drawing of lines.

The 21st must be defined by the erasing of them.

From South Asia to the Middle East, from Africa to Eastern Europe, the modern world still lives under the shadow of borders drawn by empires that no longer exist. These lines — carved by rulers and colonial administrators — continue to divide people who share languages, faiths, and bloodlines. And yet, the solution is not war, nor conquest. Humanity has tried both for centuries, and the results have been the same: ruins, refugees, and resentment.

The only viable way forward is maximum peace, maximum stability, and maximum trade. But that is easier said than done — especially when mistrust runs deep and old wounds refuse to heal.

War and Conquest Are No Longer Options

There was a time when conquest was considered a path to glory. Empires rose and fell on the backs of armies. But in the nuclear, globalized, and interconnected world of the 21st century, war has become economically suicidal and morally indefensible.

The tools of domination have changed — data, capital, and influence have replaced swords and tanks. No modern nation can invade another without triggering global economic aftershocks. From Ukraine to Gaza, the world has seen how every war today creates not victors, but vacuums.

What is left behind after war?

Burned cities, broken economies, and generations who inherit bitterness instead of opportunity.

The lesson of our age is clear: conquest has no place in a connected world.

Trade: The Modern Bridge Across Ancient Divides

Trade is not merely an economic activity — it is a peace process disguised as commerce.

When two regions trade, they talk. When they talk, they begin to understand. When they understand, they stop killing each other.

This is the fundamental logic that turned France and Germany, once mortal enemies, into partners who co-founded the European Union.

It is the same principle that transformed Vietnam and the United States, once divided by napalm and ideology, into major trading allies.

Could the same happen in South Asia? Could trade turn hostility into cooperation between India and Pakistan, or Afghanistan and Pakistan, or even Israel and its neighbors?

It’s possible — but it demands courage, leadership, and patience.

The Hardest Border on Earth: India and Pakistan

Nowhere is this challenge more visible than between India and Pakistan — arguably the world’s most militarized and emotionally charged border. Two nations born from one civilization, two peoples divided by politics and history, and two nuclear powers locked in a rivalry that has lasted for over seven decades.

Since 1947, the subcontinent has fought four wars, suffered terror attacks, and endured endless cycles of distrust.

Yet, every time trade and dialogue resumed — even briefly — there were glimmers of hope.

In the early 2000s, when cross-border trade routes reopened and trucks began moving between Punjab and Sindh, border villages saw prosperity they hadn’t known for decades. Joint cultural events between Lahore and Amritsar rekindled a shared sense of identity. Ordinary people, not politicians, reminded the world that peace is profitable.

But each time, politics pulled the plug. Every incident, every provocation, every attack became an excuse to close the gates again.

The lesson?

Peace cannot be built by governments alone. It must be demanded — and sustained — by the people.

Peace and Stability: The Only True Power

In today’s world, stability is the new strength.

Nations that prioritize peace and trade grow faster, attract investment, and command global respect.

Nations that cling to enmity stagnate in military budgets and diplomatic isolation.

Look at Singapore, Switzerland, or the UAE — small countries that turned peace into prosperity. Their real weapon is predictability. Their real influence comes from being safe spaces for trade, dialogue, and diplomacy.

For historically divided regions like South Asia, the Middle East, or Central Africa, peace is not a luxury — it’s survival.

The future will belong not to those who win wars, but to those who avoid them altogether.

The Way Forward: A Blueprint for Divided Regions

-

Normalize Trade Before Talks

Start with commerce, not ideology. Trucks, not tanks, should cross borders first. -

Encourage Regional Infrastructure

Shared roads, energy grids, and digital networks make war impractical and peace profitable. -

Build People-to-People Channels

Cultural exchanges, tourism, and student programs can do what diplomats often cannot — humanize the “enemy.” -

Media Cooperation Over Manipulation

Both sides must fight propaganda and replace fear with understanding. -

Use Technology for Transparency

Digital trade platforms and blockchain can reduce corruption and build trust in cross-border transactions.

Conclusion: The Future Without Frontiers

The colonialists drew the lines.

We must now learn to live beyond them.

The world cannot afford to remain hostage to 19th-century borders in a 21st-century reality. The way out is not through the battlefield, but through markets, dialogue, and shared prosperity.

Peace is not passive — it is a deliberate act of courage.

And trade is not just business — it is the architecture of coexistence.

When nations finally realize that their future is richer together than apart, perhaps the ghosts of the past will fade —

and the lines that once divided us will become the roads that unite us.

रास्ता क्या है: युद्ध नहीं, शांति और व्यापार ही भविष्य हैं

भूमिका: कृत्रिम सीमाओं का युग

20वीं सदी रेखाएँ खींचने की सदी थी,

21वीं सदी उन्हें मिटाने की सदी होनी चाहिए।

दक्षिण एशिया से लेकर मध्य पूर्व तक, अफ्रीका से लेकर पूर्वी यूरोप तक — आज की दुनिया अब भी उन सीमाओं के साये में जी रही है जिन्हें कभी ऐसे साम्राज्यों ने खींचा था जो अब अस्तित्व में भी नहीं हैं। ये रेखाएँ — जिन्हें औपनिवेशिक अधिकारियों ने डिनर टेबल पर स्केल और पेन से बनाया था — अब भी उन लोगों को बाँट रही हैं जो भाषा, धर्म और खून से एक हैं।

लेकिन अब समाधान युद्ध नहीं है, न ही विजय। मानवता सदियों से इन दोनों रास्तों को आजमा चुकी है — और हर बार नतीजा वही रहा है: खण्डहर, शरणार्थी, और घृणा।

आज का रास्ता सिर्फ़ एक है — अधिकतम शांति, अधिकतम स्थिरता, और अधिकतम व्यापार।

पर यह कहना आसान है, करना मुश्किल — ख़ासकर तब जब अविश्वास गहराई तक फैला हो और पुराने ज़ख्म अब भी ताज़ा हों।

युद्ध और विजय अब विकल्प नहीं रहे

एक समय था जब विजय को गौरव का प्रतीक माना जाता था। साम्राज्य सेनाओं के दम पर बनते और टूटते थे। लेकिन 21वीं सदी की परमाणु और वैश्वीकृत दुनिया में युद्ध अब आर्थिक आत्महत्या और नैतिक दिवालियापन बन चुका है।

अब शक्ति की परिभाषा बदल चुकी है — तलवारों और टैंकों की जगह अब डेटा, पूँजी और प्रभाव ने ले ली है। कोई भी आधुनिक राष्ट्र अब किसी दूसरे देश पर आक्रमण नहीं कर सकता बिना पूरी वैश्विक अर्थव्यवस्था को हिला दिए।

यूक्रेन से लेकर ग़ज़ा तक, हर संघर्ष ने दिखाया है कि आज के युद्धों में विजेता नहीं बनते — बस शून्य पैदा होता है।

युद्ध के बाद क्या बचता है?

जले हुए शहर, टूटी अर्थव्यवस्था, और पीढ़ियाँ जो अवसर नहीं, नफ़रत विरासत में पाती हैं।

सीख स्पष्ट है — विजय अब प्रगति का रास्ता नहीं, विनाश का पर्याय है।

व्यापार: शांति का नया पुल

व्यापार केवल आर्थिक लेनदेन नहीं है — यह एक प्रकार की शांति प्रक्रिया है जो वाणिज्य के रूप में छिपी है।

जब दो क्षेत्र व्यापार करते हैं, वे बातचीत करते हैं।

जब वे बातचीत करते हैं, वे समझने लगते हैं।

और जब वे समझते हैं, तो वे लड़ना बंद कर देते हैं।

यही तर्क था जिसने फ़्रांस और जर्मनी जैसे दुश्मनों को एक-दूसरे के साझेदार में बदला — जिन्होंने बाद में यूरोपीय संघ (European Union) की नींव रखी।

यही सिद्धांत वियतनाम और अमेरिका पर भी लागू हुआ — जो कभी युद्ध में आमने-सामने थे, आज व्यापारिक सहयोगी हैं।

क्या ऐसा दक्षिण एशिया में संभव है?

क्या भारत और पाकिस्तान, अफगानिस्तान और पाकिस्तान, या यहाँ तक कि इज़राइल और उसके पड़ोसी व्यापार के ज़रिए अपने मतभेद मिटा सकते हैं?

संभव है — पर इसके लिए नेतृत्व, धैर्य और साहस चाहिए।

दुनिया की सबसे कठिन सीमा: भारत और पाकिस्तान

दुनिया में शायद ही कोई सीमा भारत–पाकिस्तान जितनी तनावपूर्ण हो।

दो राष्ट्र, जो एक ही सभ्यता से निकले;

दो लोग, जो एक ही संस्कृति, भाषा और इतिहास साझा करते हैं;

और दो परमाणु शक्तियाँ, जो पिछले सात दशकों से अविश्वास की दीवारों में क़ैद हैं।

1947 के बाद से दोनों देशों ने चार युद्ध लड़े, असंख्य आतंकी हमले झेले, और संवाद के हर प्रयास को राजनीति की बलि चढ़ते देखा।

फिर भी जब-जब व्यापार के रास्ते खुले, उम्मीद की रोशनी दिखी।

2000 के दशक में जब सीमा पार ट्रक चलने लगे, तो पंजाब और सिंध के गाँवों में दशकों बाद समृद्धि लौटी।

लाहौर–अमृतसर के सांस्कृतिक कार्यक्रमों ने याद दिलाया कि लोग अब भी एक-दूसरे को “पराया” नहीं मानते।

लेकिन हर बार, किसी राजनीतिक घटना ने इस पुल को तोड़ दिया।

हर हमला, हर उकसावा — संवाद बंद करने का बहाना बन गया।

सच्चाई यह है:

शांति केवल सरकारों से नहीं बनेगी — इसे जनता को माँगना और बनाए रखना होगा।

शांति और स्थिरता: असली ताक़त

आज की दुनिया में स्थिरता ही नई शक्ति है।

जो देश शांति और व्यापार को प्राथमिकता देते हैं, वे तेज़ी से बढ़ते हैं, निवेश खींचते हैं, और सम्मान अर्जित करते हैं।

जो देश दुश्मनी पकड़े रहते हैं, वे अपनी ऊर्जा युद्ध की तैयारी में बर्बाद करते हैं।

देखिए सिंगापुर, स्विट्ज़रलैंड, और संयुक्त अरब अमीरात (UAE) को — छोटे देश जिन्होंने शांति को समृद्धि में बदला।

उनका असली हथियार “अनुमानित स्थिरता” है।

उनका असली प्रभाव है “विश्वसनीयता।”

दक्षिण एशिया, मध्य पूर्व या मध्य अफ्रीका जैसे विभाजित क्षेत्रों के लिए, शांति कोई विलासिता नहीं — जीवन का आधार है।

भविष्य उनका है जो युद्ध जीतेंगे नहीं, बल्कि युद्ध टालेंगे।

आगे का रास्ता: विभाजित क्षेत्रों के लिए एक खाका

-

बातचीत से पहले व्यापार को सामान्य करें

टैंक नहीं, ट्रक सीमा पार करें। विचारधारा से पहले अर्थव्यवस्था को जोड़े। -

क्षेत्रीय बुनियादी ढाँचा साझा करें

सड़कें, ऊर्जा नेटवर्क और डिजिटल कनेक्टिविटी युद्ध को असंभव बनाती हैं। -

जनता-से-जनता के रिश्ते बढ़ाएँ

सांस्कृतिक आदान-प्रदान, पर्यटन, और छात्र कार्यक्रम वह कर सकते हैं जो राजनयिक नहीं कर पाते — “दुश्मन” को इंसान बनाना। -

मीडिया में सहयोग, प्रचार नहीं

डर और नफ़रत फैलाने के बजाय समझ और भरोसे को बढ़ावा दें। -

तकनीक से पारदर्शिता लाएँ

डिजिटल व्यापार और ब्लॉकचेन जैसे माध्यम सीमा पार भ्रष्टाचार और अविश्वास को घटा सकते हैं।

निष्कर्ष: सीमाओं के बिना भविष्य

औपनिवेशिक शक्तियों ने रेखाएँ खींचीं,

अब हमें उनके पार जीना सीखना होगा।

दुनिया 19वीं सदी की सीमाओं की क़ैदी बनकर 21वीं सदी में नहीं चल सकती।

भविष्य का रास्ता युद्धभूमि से नहीं, बाज़ार, संवाद और साझा समृद्धि से होकर जाता है।

शांति कोई निष्क्रिय अवस्था नहीं — यह साहस का सक्रिय कर्म है।

और व्यापार केवल व्यवसाय नहीं — यह सह-अस्तित्व की वास्तुकला है।

जब राष्ट्र यह समझ लेंगे कि

उनका भविष्य अलग-अलग नहीं, बल्कि साथ-साथ अधिक समृद्ध है,

तब शायद अतीत की आत्माएँ शांत होंगी —

और वे रेखाएँ, जिन्होंने हमें बाँटा था,

उन्हीं सड़कों में बदल जाएँगी जो हमें जोड़ेंगी।

No comments:

Post a Comment