The Minsk Agreements were two sets of accords signed in 2014 and 2015 to address the conflict in eastern Ukraine between Russian-backed separatists and Ukrainian forces in the Donbas region. Their goal was to establish a ceasefire and lay the groundwork for a political resolution. Here's a concise overview:

Minsk I (September 5, 2014)

Signed in Minsk, Belarus, by representatives of Ukraine, Russia, the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics (DPR/LPR), and the OSCE (Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe). It followed intense fighting, particularly after Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the outbreak of conflict in Donbas.

Key Provisions:

-

Ceasefire: Immediate bilateral ceasefire.

-

Monitoring: OSCE to monitor and verify the ceasefire.

-

Decentralization: Ukraine to adopt laws granting special status to certain Donbas regions, including provisions for local self-governance.

-

Amnesty: Pardon for individuals involved in the conflict.

-

Prisoner Exchange: Release of hostages and detainees.

-

Humanitarian Aid: Delivery and distribution of aid to affected areas.

-

Elections: Local elections in Donbas under Ukrainian law.

-

Withdrawal of Forces: Removal of illegal armed groups, military equipment, and foreign fighters from Ukrainian territory.

-

Border Control: Restoration of Ukrainian control over its border with Russia.

-

Economic and Social Recovery: Measures to restore economic ties and rebuild Donbas.

Outcome: The ceasefire was fragile, with frequent violations by both sides. Many provisions—especially regarding decentralization and elections—were not implemented.

Minsk II (February 12, 2015)

Signed after Minsk I failed to stop the fighting, particularly following major clashes in Debaltseve. It was negotiated by the Normandy Format (Ukraine, Russia, France, and Germany) and signed by the same parties as Minsk I.

Key Provisions (13-point plan):

-

Immediate Ceasefire: Effective from February 15, 2015.

-

Withdrawal of Heavy Weapons: Both sides to pull back heavy weaponry to create a 50–140 km buffer zone, depending on the weapon type.

-

OSCE Monitoring: Oversight of the ceasefire and withdrawal process.

-

Dialogue on Elections: Begin discussions on local elections in Donbas and modalities for self-governance.

-

Amnesty: Pardon for participants in the conflict.

-

Prisoner Exchange: "All for all" exchange of hostages and detainees.

-

Humanitarian Access: Safe and unhindered delivery of humanitarian aid.

-

Special Status: Constitutional reforms in Ukraine to grant special status to certain Donbas regions.

-

Elections: Local elections in Donbas to be held under Ukrainian law with OSCE supervision.

-

Withdrawal of Foreign Forces: Removal of all foreign troops, military equipment, and mercenaries under OSCE oversight.

-

Border Control: Ukraine to regain full control of its border with Russia after local elections and constitutional reforms (by the end of 2015).

-

Economic Recovery: Restoration of social payments and economic links with Donbas.

-

Normandy Format Oversight: Regular meetings to ensure implementation.

Outcome: While Minsk II helped reduce some fighting, it failed to secure a lasting ceasefire. Core issues—such as elections, border control, and decentralization—remained unresolved due to disputes over sequencing. Ukraine demanded border control before political concessions, whereas Russia and the separatists insisted on holding elections first. Ongoing violations persisted, and the conflict continued until Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022.

Context and Challenges

-

The agreements were criticized for their vague language and conflicting interpretations.

-

Ukraine viewed them as steps toward reintegration, while Russia and the separatists interpreted them as legitimizing DPR/LPR autonomy.

-

Implementation was hampered by mistrust, continued skirmishes, and political deadlock.

-

The agreements are now widely regarded as defunct following Russia’s 2022 invasion and subsequent annexation of Donbas territories.

The Istanbul Talks of 2022 refer to a series of negotiations between Ukraine and Russia held in Istanbul, Turkey, primarily during March and April 2022, shortly after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24. These talks aimed to secure a ceasefire and lay the foundation for a potential peace agreement. While they did not produce a final signed treaty, they resulted in a draft framework commonly referred to as the Istanbul Communiqué, which outlined potential settlement terms. Below is a summary of the key provisions, based on available sources:

Key Provisions of the Istanbul Communiqué (March 29, 2022)

According to Ukrainian negotiators and various reports, the draft agreement included the following elements, though none were finalized or mutually agreed upon:

1. Ukrainian Neutrality

-

Ukraine would adopt permanent neutrality, enshrined in its constitution, prohibiting membership in military alliances like NATO.

-

Ukraine would not host foreign military bases, personnel, or weapons—including NATO troops and trainers.

-

Ukraine could pursue European Union membership, which Russia reportedly agreed to "facilitate" in some drafts—marking a shift from its earlier opposition to Ukraine's EU integration.

2. Military Restrictions

-

Russia proposed substantial limits on Ukraine’s military, including reducing active-duty troops to 85,000–100,000 (from ~250,000), capping tanks, missiles, aircraft, and limiting missile ranges to 40 km.

-

Ukraine pushed back on these limitations, especially troop caps, and insisted on maintaining a large reserve force.

-

Discussions on military force size were deferred to a potential future meeting between Presidents Zelenskyy and Putin.

3. Security Guarantees

-

A multilateral security guarantee system was proposed, involving the five permanent UN Security Council members (U.S., Russia, China, U.K., and France), among others.

-

Guarantors would be obligated to intervene militarily if Ukraine were attacked again, loosely modeled on NATO’s Article 5.

-

Russia demanded veto power over such interventions, which Ukraine and Western partners rejected as unworkable and reminiscent of the UN’s veto gridlock.

-

Critics noted that the proposed guarantees lacked binding enforcement mechanisms, undermining Ukraine’s security.

4. Territorial Issues

-

Crimea: The status of Crimea, annexed by Russia in 2014, would be deferred for 10–15 years of negotiations. Ukraine would refrain from using force to reclaim it, while not formally recognizing Russia’s annexation.

-

Donbas: The future of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions—controlled in part by Russian-backed separatists since 2014—was left for further negotiation. Some drafts suggested autonomy within Ukraine, though Russia reportedly sought full recognition of the regions as Russian territory, which Ukraine rejected.

5. Ceasefire and Withdrawals

-

A full, unconditional ceasefire covering land, sea, and air operations was proposed—initially for 30 days and extendable.

-

Russia would withdraw its forces to pre-invasion positions (as of February 23, 2022), retaining control of parts of Donbas and Crimea. Ukraine demanded that such withdrawal not be seen as legitimizing any territorial claims.

-

Provisions included an “all-for-all” prisoner exchange and the return of deported or forcibly displaced individuals.

6. Other Provisions

-

Ukraine proposed Russian reparations for war damages, which Russia rejected.

-

Russia demanded official status for the Russian language in Ukraine and constitutional amendments to formalize neutrality—both opposed by Ukraine.

-

A potential Zelenskyy–Putin summit was envisioned to resolve remaining issues and finalize any agreement.

Why the Talks Failed

The Istanbul talks collapsed in April 2022 for several key reasons:

-

Bucha Massacre: Revelations of Russian atrocities in Bucha and Irpin hardened Ukrainian public opinion and made political compromise increasingly untenable.

-

Western Influence: Reports suggest Western leaders—especially then-U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson—encouraged Ukraine to abandon the talks, promising military support for victory. Ukraine had not consulted the U.S. before issuing the communiqué, and Western powers were reluctant to commit to direct security guarantees.

-

Russian Demands: Russia’s insistence on veto powers, major Ukrainian military reductions, and territorial concessions was seen as tantamount to demanding Ukraine’s surrender.

-

Lack of Trust: Ukraine cited Russia’s prior violations of agreements (e.g., the Minsk Accords) and later described the Istanbul terms as a “Russian ultimatum,” not genuine negotiation.

-

Strategic Shift: Ukraine’s battlefield gains in Kharkiv and Kherson, along with increased Western military support, shifted Kyiv’s calculus toward a military solution over diplomacy.

Context and Aftermath

-

While some saw the Istanbul Communiqué as a potential breakthrough, critics viewed it as a "blueprint for Ukraine’s capitulation," leaving the country disarmed and vulnerable to future Russian aggression.

-

Russia later claimed the talks could form the basis for a peace agreement, while Ukraine dismissed them as unacceptable. In December 2024, Zelenskyy publicly stated that the draft amounted to surrender.

-

In 2025, some U.S. officials (such as envoy Steve Witkoff) suggested revisiting the Istanbul framework, though others—including envoy Keith Kellogg—argued that circumstances had changed too much for the terms to remain relevant.

Note on Sources

This summary is based on draft documents and public reports from The New York Times, Reuters, Foreign Affairs, and other sources, including statements by negotiators. The drafts from March 17 and April 15, 2022, represented competing proposals rather than a finalized deal. Russia’s past violations of agreements, including the Minsk Accords, further eroded trust in any Istanbul-based peace framework.

Relation to the Minsk Agreements

Unlike the Minsk Agreements (2014–2015), which addressed the limited Donbas conflict and were signed under pressure with separatist involvement, the Istanbul Talks focused on the broader 2022 invasion and involved direct negotiations between Ukraine and Russia. Whereas Minsk emphasized decentralization and local elections, Istanbul centered on neutrality and international security guarantees. The failure of Minsk, largely due to Russian non-compliance, influenced Ukraine’s deep skepticism toward the Istanbul process.

Circumstances of Crimea’s Invasion (2014)

The invasion and annexation of Crimea by Russia occurred between February and March 2014, following a period of political upheaval in Ukraine. The key circumstances leading to the event were:

1. Euromaidan Protests and Political Upheaval

-

In late 2013, mass protests—known as the Euromaidan or Maidan Uprising—erupted across Ukraine after President Viktor Yanukovych, under pressure from Russia, suspended an Association Agreement with the European Union in favor of closer ties with Moscow.

-

The protests, centered in Kyiv’s Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square), called for European integration, democratic reforms, and an end to systemic corruption. By February 2014, violent clashes between protesters and security forces had led to over 100 deaths (the “Heavenly Hundred”).

-

On February 21, 2014, Yanukovych signed a European-mediated agreement with opposition leaders to hold early elections. However, he fled Kyiv the following day as protests intensified, effectively abandoning his post. Ukraine’s parliament voted to remove him and appointed an interim government, with Oleksandr Turchynov as acting president.

2. Russian Strategic Interests

-

Russia viewed Ukraine’s pivot toward the West as a threat to its influence in the post-Soviet region, particularly after the Euromaidan movement signaled a rejection of Russian-led alignment.

-

Crimea held immense strategic value, especially as the home of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet in Sevastopol, leased from Ukraine until 2042. Losing Crimea would weaken Russia’s naval capabilities and regional presence.

-

Crimea’s majority ethnic Russian population (about 58%, per the 2001 census) and large Russian-speaking community provided Russia with a pretext for intervention under the guise of protecting Russian speakers.

3. Pretext for Intervention

-

Russia claimed the removal of Yanukovych was an illegal coup backed by the West, endangering Russian-speaking communities and Russia’s interests in Crimea.

-

Pro-Russian demonstrations—some orchestrated by Russian operatives—called for secession or Moscow’s protection, laying the groundwork for intervention.

-

On February 27, 2014, Russian President Vladimir Putin and his Security Council decided to “begin work on returning Crimea to Russia,” a fact later revealed in a 2015 documentary.

How the Invasion Was Carried Out

The invasion is widely considered a textbook example of "hybrid warfare," combining covert military operations, disinformation, cyberattacks, and political subversion. It unfolded quickly and effectively:

1. Deployment of “Little Green Men”

-

On February 27, 2014, armed men in unmarked uniforms—later confirmed to be Russian special forces and Spetsnaz—seized key government buildings in Simferopol, including the Crimean parliament and the Council of Ministers.

-

These “little green men” blockaded Ukrainian military bases, airports (including Simferopol and Sevastopol), and other critical infrastructure, cutting off Ukrainian reinforcements.

-

Russia initially denied involvement, claiming they were local "self-defense units." In 2015, Putin admitted these forces were Russian military personnel acting under his orders.

2. Control of Strategic Assets

-

Russian forces, including the Black Sea Fleet stationed in Crimea, quickly took control of military installations, ports, airfields, and communication centers.

-

Ukrainian garrisons were encircled, cut off from supplies and communication, and pressured to surrender. Many soldiers, under-equipped and demoralized, eventually complied.

-

By early March, Russia had de facto control of Crimea with minimal armed resistance.

3. Political Manipulation and Referendum

-

Under Russian military presence, the Crimean parliament appointed pro-Russian politician Sergey Aksyonov as regional leader.

-

On March 6, 2014, the parliament scheduled a referendum on Crimea’s status, presenting a binary choice that heavily favored joining Russia.

-

The referendum, held on March 16, 2014, was widely condemned as illegitimate. It was conducted under military occupation, lacked credible international observation, and was marred by coercion and ballot irregularities. Official results claimed 96.8% voted to join Russia, with an 83% turnout—figures disputed by independent observers.

-

On March 17, Crimea’s parliament declared independence and requested annexation. Putin signed a treaty the next day, formalizing annexation on March 21, 2014.

4. Disinformation and Propaganda

-

Russia deployed an aggressive propaganda campaign to justify the intervention, portraying it as a humanitarian mission to protect ethnic Russians from “fascist” Ukrainian nationalists.

-

False claims of persecution and threats to Russian speakers were widely circulated in state-controlled media, though no credible evidence supported these assertions.

-

Russian-backed militias staged demonstrations to simulate popular support for annexation.

5. International Context

-

Ukraine’s interim government was politically unstable, and its military unprepared for such a swift operation.

-

Western responses were limited to condemnation and targeted sanctions against Russian officials and entities. No military assistance was provided to Ukraine at the time.

-

The invasion violated the 1994 Budapest Memorandum, in which Russia, the U.S., and the U.K. had pledged to respect Ukraine’s territorial integrity in exchange for Ukraine giving up its nuclear weapons.

Key Details and Outcomes

-

Timeline: The operation began on February 27 and concluded with formal annexation by March 18, 2014.

-

Casualties: The invasion saw minimal bloodshed. A few Ukrainian personnel were killed (e.g., Serhiy Kokurin on March 18), and some activists were abducted or tortured.

-

Ukrainian Military Response: Ukraine had about 18,000 troops in Crimea. Around 50% defected to Russia, while others surrendered or withdrew. Evacuation began in late March.

-

International Reaction: The UN General Assembly passed Resolution 68/262 on March 27, affirming Ukraine’s sovereignty and declaring the referendum invalid (100 in favor, 11 against, 58 abstentions). Only a handful of countries—such as North Korea and Syria—recognized Russia’s annexation.

-

Aftermath: Crimea remains under Russian control. The annexation fueled the war in Donbas and laid the groundwork for Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022.

Relation to the Istanbul Talks (2022)

During the 2022 Istanbul negotiations, Crimea’s status remained unresolved. The draft communiqué proposed a 10–15-year moratorium on the issue, during which Ukraine would refrain from using force, and Russia would retain de facto control. No agreement was reached. Ukraine has since declared its intention to liberate Crimea, viewing the annexation as a gross violation of international law.

NATO Expansion After 1991

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, NATO underwent significant eastward expansion, incorporating former Soviet-aligned states and former Soviet republics into the alliance. This expansion was driven by a combination of post–Cold War geopolitical shifts, the desire of Eastern European nations to secure protection against potential Russian aggression, and NATO’s open-door policy. Below is an overview of NATO’s expansion after 1991:

1. Context of Expansion

-

The end of the Cold War and the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact in 1991 created a security vacuum in Eastern Europe. Former communist states sought integration with Western institutions—particularly NATO and the EU—to ensure political stability, democracy, and protection from a resurgent Russia.

-

NATO’s 1990 London Declaration marked a shift from confrontation to cooperation, encouraging former adversaries to engage through initiatives like the Partnership for Peace (PfP), launched in 1994.

-

Russia, weakened in the 1990s, initially participated in the PfP and signed the NATO-Russia Founding Act in 1997, which established a framework for cooperation. However, as Russia regained strength under Vladimir Putin, it grew increasingly hostile toward NATO’s expansion.

2. Waves of NATO Enlargement

-

1999: The first post–Cold War expansion included Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic, all former Warsaw Pact members. They joined on March 12, 1999, seeking NATO’s Article 5 collective defense guarantees.

-

2004: The largest single expansion wave added seven countries: Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia. The inclusion of the Baltic states—former Soviet republics bordering Russia—heightened Moscow’s concerns.

-

2009: Albania and Croatia joined, consolidating NATO’s position in the Balkans.

-

2017: Montenegro became a member, extending NATO’s presence in the Western Balkans.

-

2020: North Macedonia joined, completing the Balkan round of expansion.

-

2023: Finland joined on April 4, doubling NATO’s land border with Russia (Finland shares a 1,340 km border). This move was prompted by Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

-

2024: Sweden joined on March 7, 2024, enhancing NATO’s strategic presence in the Baltic Sea region.

3. Key Statistics

-

NATO expanded from 16 members in 1991 to 32 by 2024.

-

The alliance’s borders moved approximately 1,000 km closer to Russia, especially through the accession of Poland and the Baltic states.

-

Each expansion wave required extensive reforms from candidate countries in the areas of democracy, governance, and military alignment, often taking several years.

4. Mechanisms and Policies

-

NATO’s Open Door Policy (Article 10 of the Washington Treaty) allows any European country capable of contributing to the alliance’s security to apply for membership.

-

The Membership Action Plan (MAP), introduced in 1999, outlines the process for aspiring members to meet NATO standards.

-

Programs like the Partnership for Peace (PfP) helped prepare countries for membership and fostered dialogue with non-member states, including Ukraine and Georgia.

Ukraine’s Constitutional Commitment to NATO and Russia’s Reaction

1. Ukraine’s NATO Aspirations

-

Ukraine began cooperating with NATO in the 1990s through the PfP program. Interest deepened after the 2004 Orange Revolution, which brought pro-Western leadership to power.

-

At the 2008 Bucharest Summit, NATO declared that Ukraine and Georgia “will become members” in the future. However, no timeline or MAP was granted, due to Russian objections and opposition from Germany and France.

-

Following the 2014 Euromaidan revolution, Russia’s annexation of Crimea, and the outbreak of war in the Donbas, Ukraine decisively pivoted westward. In 2017, Ukraine’s parliament passed legislation prioritizing NATO integration.

-

On February 7, 2019, Ukraine amended its constitution to enshrine its strategic objective of joining NATO and the EU, marking a symbolic and legal break from Russian influence.

2. Russia’s Reaction and Historical Context

-

Strategic Concerns: Russia views NATO’s expansion—especially into Ukraine—as a direct threat to its national security. Ukraine shares a 2,295 km border with Russia, and its accession would place NATO infrastructure close to Russia’s core. Moscow has long argued that NATO expansion violates informal post–Cold War assurances, though no formal agreement prohibited it.

-

Historical Analogies to Hitler and Napoleon:

-

Putin and other Russian leaders have drawn comparisons between NATO’s expansion and historic Western invasions—Napoleon’s 1812 campaign and Hitler’s 1941 invasion. Both advanced through territories that include modern Ukraine.

-

In speeches from 2014 and 2022, Putin framed NATO as a modern-day threat akin to past Western aggressors, asserting that Ukraine's NATO membership would undermine Russia’s “strategic depth.”

-

In his February 21, 2022 speech, Putin claimed NATO expansion and Ukraine’s constitutional commitment were part of a Western conspiracy to encircle Russia—citing this as a justification for the invasion.

-

-

Specific Sticking Points:

-

Ukraine’s 2019 constitutional amendment was viewed by Russia as a permanent break from neutrality, eliminating the possibility of Ukraine serving as a geopolitical buffer state.

-

Russia’s 2021–2022 ultimatums, delivered through draft treaties, demanded legally binding guarantees from the U.S. and NATO to halt further expansion, specifically excluding Ukraine. Russia also sought the withdrawal of NATO forces from countries that joined after 1997.

-

The potential deployment of NATO bases, missile systems, or troops in Ukraine exacerbated Russian fears, especially given Kyiv’s geographic proximity to Moscow (around 500 km).

-

3. Why Ukraine’s NATO Commitment Became a Flashpoint

-

Geopolitical Rivalry: Ukraine’s westward alignment threatened Russia’s influence in the post-Soviet space and initiatives like the Eurasian Economic Union.

-

Domestic Politics in Russia: Putin has used the perceived NATO threat to bolster domestic support and present himself as the defender of Russian sovereignty.

-

Military Implications: Ukraine’s NATO membership would invoke Article 5, potentially drawing NATO into direct conflict with Russia. Even without formal membership, NATO’s training missions and arms shipments to Ukraine since 2014 were perceived in Moscow as creeping integration.

-

Istanbul Talks (2022): During the negotiations, Russia demanded Ukraine abandon its NATO ambitions and adopt constitutional neutrality. Ukraine countered with a proposal for neutrality in exchange for international security guarantees, but Russia rejected this as inadequate, contributing to the talks' collapse.

Relation to Historical Invasions

-

Napoleon (1812): Napoleon’s Grand Army invaded Russia through present-day Ukraine, culminating in the Battle of Borodino and the burning of Moscow. The campaign reinforced the strategic value of buffer territories.

-

Hitler (1941): Nazi Germany’s Operation Barbarossa invaded the Soviet Union through Ukraine and Belarus, causing massive destruction and over 20 million Soviet deaths. Ukraine was a central battleground.

-

While these analogies are used by Russian leaders to evoke fear and justify aggression, NATO is a defensive alliance, not an expansionist empire. Nevertheless, these historical narratives are deeply rooted in Russian memory and political rhetoric.

Current Status (as of June 2025)

-

Ukraine remains a NATO partner but is not yet a member. At the 2024 Washington Summit, NATO reaffirmed that Ukraine’s path to membership is “irreversible,” but no MAP or timeline was provided due to the ongoing war.

-

Russia’s 2022 invasion was, in part, motivated by Ukraine’s NATO aspirations, which Putin cited as a casus belli. Ironically, the invasion has strengthened NATO—prompting Finland and Sweden to join, and increasing NATO’s military engagement with Ukraine.

-

Ukraine’s constitutional commitment to NATO remains intact, and President Zelenskyy has rejected neutrality as a viable concession—especially after Russia’s 2022 annexation of four Ukrainian regions.

Russia’s Political System, Leadership, and Prospects for Change

Below, we address your questions about Russia’s political system, Vladimir Putin’s leadership, the death of Alexei Navalny, the potential for Russia to join NATO, the conditions under which Putin’s regime could collapse, and the possibility of a coup, including key figures who could initiate one. Each section is concise yet comprehensive, drawing on current information and critically examining the context.

Why Is Russia Not a Democracy Despite Holding Elections?

Although Russia holds regular elections, it is not considered a democracy due to the absence of key democratic features such as free and fair elections, political pluralism, an independent media, and the rule of law. Its system is often described as a "managed democracy" or “sovereign democracy”—a façade to legitimize authoritarian rule. Key issues include:

-

Controlled Elections: The Kremlin manipulates elections through tactics like ballot stuffing, voter suppression, and disqualification of legitimate challengers. For instance, opposition leader Alexei Navalny was barred from the 2018 election due to politically motivated charges. In the 2024 election, Putin secured 87% of the vote in a process labeled a "pantomime," with credible challengers like Boris Nadezhdin excluded.

-

Suppression of Opposition: Opposition figures are routinely jailed, exiled, or killed. Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) was declared “extremist” in 2021, barring its members from political participation. Other critics, such as Boris Nemtsov (assassinated in 2015), faced lethal consequences.

-

Media Control: The Kremlin dominates the media landscape, pushing pro-Putin narratives. Independent outlets have been shuttered or forced into exile—particularly after the 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

-

Judicial Subservience: Courts function as tools of the regime, issuing politically motivated convictions. Navalny’s repeated prosecutions and sentences illustrate how the judiciary is used to neutralize dissent.

-

Constitutional Manipulation: In 2020, constitutional changes enabled Putin to potentially remain in power until 2036, eliminating term limits and undermining democratic accountability.

These features classify Russia as authoritarian. Elections are staged rituals, not mechanisms for meaningful political change.

Why Is Putin Called a Dictator?

Vladimir Putin is widely labeled a dictator due to his consolidation of power, elimination of institutional checks, and aggressive suppression of dissent. Characteristics include:

-

Centralized Control: Putin dominates all branches of government, security services, and the state-controlled economy. The United Russia party and nominal “opposition” parties are Kremlin-aligned.

-

Longevity: In power since 2000 (excluding a nominal presidency swap with Medvedev from 2008–2012), Putin has manipulated elections and the constitution to stay in office longer than many Soviet leaders.

-

Repression: His regime has employed poisoning, imprisonment, and assassination to silence critics—Navalny (2020, 2024), Nemtsov (2015), and Prigozhin (2023) are notable examples.

-

Cult of Personality: State media portrays Putin as a near-mythic figure and national savior, reinforcing ultra-nationalist and militarist narratives.

-

Corruption: Putin presides over a kleptocracy. Navalny’s investigations revealed elite enrichment schemes—most famously the “Palace for Putin” exposé.

Putin’s Russia meets the criteria of a personalist autocracy, as confirmed by numerous political analysts and institutions.

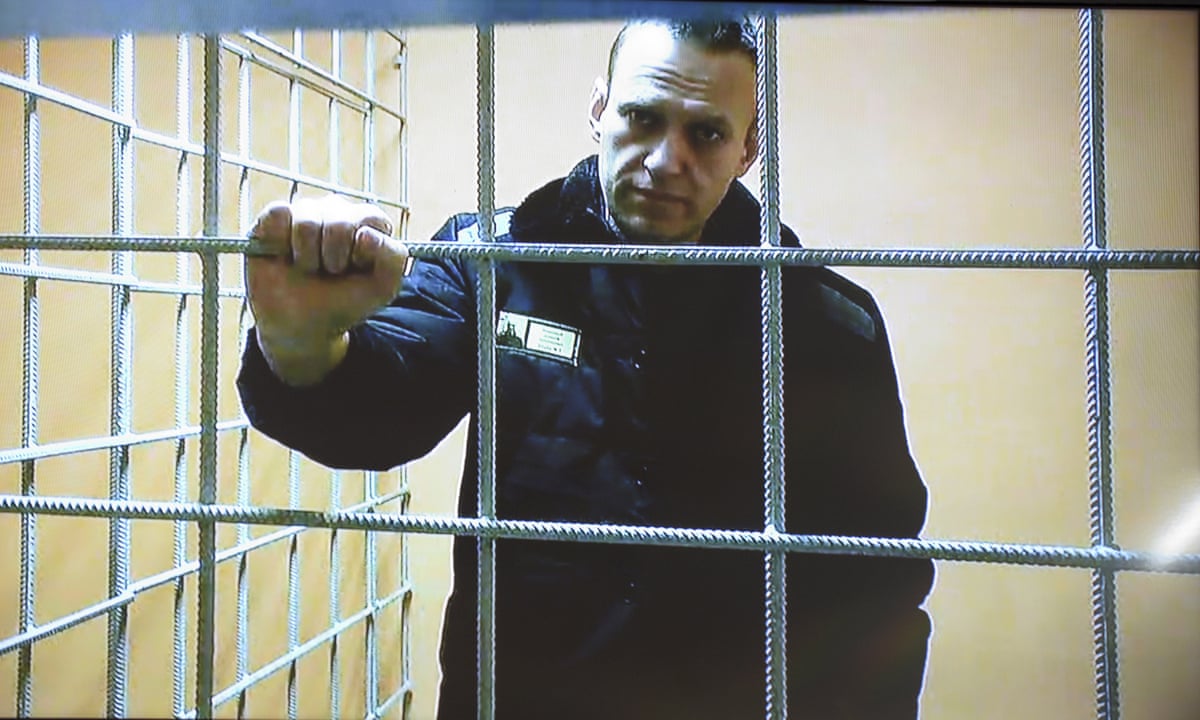

Circumstances of Alexei Navalny’s Death

Alexei Navalny, Russia’s most prominent opposition figure, died on February 16, 2024, in the Arctic prison colony “Polar Wolf.” While the Kremlin claims he died of natural causes, strong evidence suggests state involvement.

-

Official Narrative: Authorities stated Navalny collapsed during a walk and died despite medical efforts. No independent autopsy or investigation was permitted.

-

Imprisonment Conditions: Navalny was serving a 19-year sentence under brutal conditions—including solitary confinement and medical neglect—after surviving a 2020 Novichok poisoning attributed to Russian security services.

-

Accusations of Murder: Western governments and human rights groups blamed the Kremlin. His widow, Yulia Navalnaya, called it a state-sanctioned assassination. The timing, just before the 2024 election, suggests a political motive to eliminate dissent.

-

Aftermath: Despite crackdowns, Navalny’s death sparked public mourning and defiance. Yulia Navalnaya emerged as a leading opposition voice, vowing to carry on his legacy.

The opacity of the investigation and Russia’s history of targeting Navalny strongly indicate his death was deliberate.

Could Russia Join NATO After Reforms?

In theory, a fully reformed Russia could apply to join NATO. However, due to its geopolitical size, history, and adversarial posture, membership is extremely unlikely.

Requirements:

-

Democracy: NATO requires democratic governance. Russia would need free elections, rule of law, and media independence.

-

Market Economy: Economic reform would mean dismantling the oligarchic system and aligning with Western norms.

-

Military Reform: Russia would have to embrace civilian control over its military and abandon aggressive doctrines.

Barriers:

-

Geopolitical Role: As a nuclear superpower, Russia resists collective security constraints and fears loss of sovereignty.

-

Historic Tensions: Decades of hostility and mutual distrust—especially over NATO’s post-1991 expansion—complicate any trust-building.

-

Imperial Mindset: Russian nationalism, territorial disputes (e.g., Crimea), and historical narratives hinder alignment with NATO’s defensive identity.

-

NATO Skepticism: Current members, particularly in Eastern Europe, would likely veto Russia’s membership.

Conclusion: A democratic Russia might revive cooperation with NATO, but full membership remains unrealistic. A strategic partnership—akin to the 1990s—would be more plausible.

Could Putin’s Regime Collapse?

Putin’s regime is durable but not invincible. Several scenarios could trigger collapse:

1. Economic Collapse

-

Sanctions and trade disruptions post-2022 have hurt Russia, though ties with China and India provide lifelines.

-

A significant drop in energy revenues or internal mismanagement could provoke unrest.

2. Military Defeat

-

A major Ukrainian victory would undermine Putin’s image as a strongman.

-

The 2023 Wagner mutiny revealed cracks in military loyalty.

3. Elite Fractures

-

The regime relies on elite loyalty and patronage. If key figures perceive Putin as a liability, they could defect.

-

A succession crisis due to illness or death could destabilize the system.

4. Mass Protests

-

Symbolic events like Navalny’s death could spark mass mobilization, though repression has kept protest levels low.

5. External Pressure

-

Greater Western support for Ukraine or Russian opposition groups could compound internal strains.

Conclusion: While the regime appears stable, a combination of war failures, economic decline, and elite defection—similar to 1991—could lead to collapse.

Could There Be a Coup? Three Likely Organizers (2025)

A coup is possible but unlikely without a major crisis. Putin maintains loyalty through surveillance, patronage, and purges. That said, potential players include:

1. Sergei Shoigu (Security Council Secretary, ex-Defense Minister)

-

Why: Shoigu has deep military ties and could act if he sees Putin as a strategic liability.

-

Limitations: His career is tied to Putin. He lacks independent political support.

2. Nikolai Patrushev (Former FSB Head, Security Adviser)

-

Why: As a key figure among the siloviki, Patrushev could pivot to preserve the system without Putin.

-

Limitations: Ideologically aligned with Putin; may prefer continuity over change.

3. Sergei Kiriyenko (Kremlin Deputy Chief of Staff)

-

Why: Oversees political management and could rally technocratic elites for a "soft" transition.

-

Limitations: Lacks military power; operates within Putin’s inner circle.

Alternative Scenarios: An unknown mid-level officer or regional leader could act under crisis conditions, but no such figure has yet emerged.

Conclusion

Russia is not a democracy. It is a highly centralized autocracy where elections are manipulated, opposition is suppressed, and power is concentrated in the hands of Vladimir Putin. His rule is sustained by repression, propaganda, and economic control. Navalny’s death exemplifies the system’s brutality.

While NATO membership for a democratic Russia is theoretically possible, geopolitical and structural obstacles make it unlikely. The regime could collapse due to war losses, economic decline, or elite splits, though the barriers to such an outcome remain formidable. A coup, while possible, would require high-level coordination under crisis conditions—none of which are fully present in 2025.

The Garden Of Last Debates (novel)

Deported (novel)

Empty Country (novel)

Trump’s Default: The Mist Of Empire (novel)

The 20% Growth Revolution: Nepal’s Path to Prosperity Through Kalkiism

Rethinking Trade: A Blueprint for a Just and Thriving Global Economy

The $500 Billion Pivot: How the India-US Alliance Can Reshape Global Trade

Trump’s Trade War

Peace For Taiwan Is Possible

Formula For Peace In Ukraine

The Last Age of War, The First Age of Peace: Lord Kalki, Prophecies, and the Path to Global Redemption

AOC 2028: : The Future of American Progressivism

Formula For Peace In Ukraine https://t.co/p53RRpxhqb

— Paramendra Kumar Bhagat (@paramendra) June 29, 2025

17/

— Paramendra Kumar Bhagat (@paramendra) June 29, 2025

🧵 Read the full blog post here:

The Minsk Agreements, The Istanbul Communiqué, Crimea, NATO Expansion, Democracy In Russia

👉 https://t.co/X3BPEHrkoq#RussiaUkraine #NATO #Navalny #Minsk #Crimea