Escalating Global Tensions: A Crossroads for International Stability

In September 2025, the world witnessed a rapid succession of geopolitical flashpoints that underscored how fragile the international system has become. Within a span of just a few weeks, Israel extended its military campaign to the Gulf by striking Hamas targets in Qatar, Russian drones violated Polish airspace during one of Moscow’s largest aerial assaults on Ukraine, and Saudi Arabia signed a historic mutual defense pact with Pakistan.

Individually, each of these events would have been alarming. Together, they paint a picture of a world sliding toward instability, where long-standing norms of sovereignty, deterrence, and mediation are being eroded. This article examines each of these crises, their interconnections, and their implications for the global order.

Israel’s Strike in Qatar: Redefining the Battlefield

On September 9, Israeli missiles struck targets in Doha, Qatar, killing at least six people and damaging multiple buildings. The attack reportedly targeted Hamas leadership figures believed to be operating from Qatari soil. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu defended the operation as a pre-emptive strike, warning that “no safe haven” would protect those threatening Israel.

For Qatar, a country that has positioned itself as a neutral broker in Middle East conflicts, the assault was a political earthquake. Doha has mediated ceasefires between Israel and Hamas, facilitated prisoner exchanges, and coordinated humanitarian aid to Gaza. By hitting inside Qatar, Israel not only violated the sovereignty of a Gulf monarchy but also jeopardized a diplomatic channel long relied upon by Washington and European capitals.

The move rattled regional geopolitics. Qatar hosts the largest U.S. military base in the Middle East, and American officials were reportedly caught off guard by the strike. Arab states condemned the attack as a dangerous precedent, while analysts warned it could push Gulf states to harden positions in future negotiations. The symbolism was stark: even a country that stayed out of direct confrontation is no longer immune from the ripple effects of the Gaza war.

Russian Drones Over Poland: NATO on the Edge

Just hours after Israel’s strike, another crisis unfolded in Europe. Between September 9 and 10, at least 19 Russian drones strayed into Polish airspace during a massive aerial offensive against Ukraine. Poland scrambled its air force, downing several drones—the first time a NATO member state has engaged in direct fire against Russian assets since the war began in 2022.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy claimed that Moscow deliberately targeted Polish territory as part of its strategy to “test NATO’s patience.” Intelligence officials remain divided on whether the incursion was intentional or the result of navigational error, but the implications were unmistakable: the war in Ukraine is no longer confined to Ukraine.

The incident reignited fears of escalation under NATO’s Article 5, which commits members to collective defense. While the alliance has so far exercised restraint, the risk of miscalculation looms. A drone crash in a Polish village in 2022 killed two civilians; this latest episode demonstrates how quickly the conflict could spiral into direct NATO–Russia confrontation. Meanwhile, Russia continues to weaponize brinkmanship, probing for alliance weaknesses as Western unity shows signs of fatigue amid economic pressures and political divisions.

The Saudi–Pakistan Defense Pact: A New Axis in the Gulf

On September 17, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif signed a landmark mutual defense agreement in Riyadh. The pact commits the two nations to come to each other’s aid in the event of external aggression. While Saudi Arabia and Pakistan have long enjoyed close security ties—Saudi financing has supported Pakistan’s economy and defense industry for decades—this marks the first time the relationship has been formalized into a treaty.

The timing is significant. With Iran continuing to expand its regional influence and U.S. security guarantees perceived as unreliable, Riyadh is hedging its bets. Pakistan, meanwhile, brings a unique deterrent to the table: nuclear weapons. Though the pact does not explicitly mention nuclear sharing, analysts warn it could pave the way for Saudi Arabia to seek a “nuclear umbrella” outside traditional Western frameworks.

For South Asia, the consequences are equally complex. If India were to clash with Pakistan, would Saudi Arabia be drawn in militarily? Could Gulf rivalries now carry nuclear undertones? Critics caution that the pact may be more symbolic than operational, but in an era of fluid alliances, symbolism itself can alter strategic calculations.

Interconnections: A Multipolar World in Flux

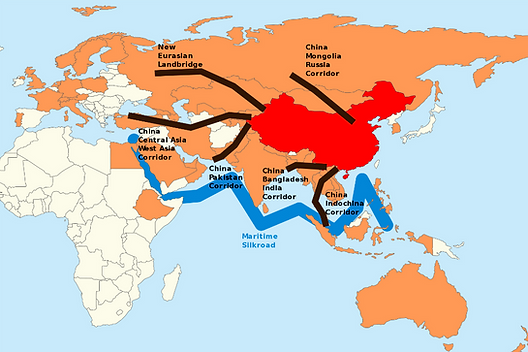

The simultaneity of these events is not coincidental. Each reflects the unraveling of a U.S.-led unipolar order and the emergence of a multipolar world where middle powers act assertively, often disregarding established norms.

-

Israel’s strike in Qatar signals a willingness to extend conflict zones beyond traditional battlefields.

-

Russia’s drone incursion into NATO airspace tests red lines in Europe.

-

The Saudi–Pakistan pact underscores the creation of new, non-Western security architectures.

Together, these developments suggest a permissive environment where states exploit distractions elsewhere to push boundaries. They also reflect a global system strained by wars in Ukraine and Gaza, contested energy supplies, fragile supply chains, and resurgent nationalism.

Implications: Between Restraint and Escalation

These “lines crossed” have three major implications for global stability:

-

Erosion of Diplomatic Sanctuaries – Qatar’s mediation role may weaken, leaving fewer neutral spaces for dialogue.

-

Normalization of Escalation – Drone incursions and cross-border strikes risk becoming routine, increasing chances of miscalculation.

-

New Security Architectures – The Saudi–Pakistan pact shows that countries are bypassing traditional alliances, raising risks of parallel defense blocs.

Still, opportunities for de-escalation remain. NATO’s measured handling of the Polish incident, and Qatar’s decision to continue humanitarian mediation despite the strike, suggest that restraint is still valued. The UN General Assembly has become a focal point for diplomatic engagement, though its ability to enforce norms is limited.

Ultimately, the crossroads of September 2025 reveals a world in transition: one where the institutions and guardrails of the 20th century no longer suffice, and where the future depends on whether major powers choose cooperation or confrontation.

बढ़ते वैश्विक तनाव: अंतरराष्ट्रीय स्थिरता के लिए एक चौराहा

सितंबर 2025 में दुनिया ने कुछ ही हफ़्तों के भीतर ऐसे भू-राजनीतिक घटनाक्रम देखे जिन्होंने यह स्पष्ट कर दिया कि अंतरराष्ट्रीय व्यवस्था कितनी नाजुक हो चुकी है। इज़रायल ने क़तर में हमास के ठिकानों पर हमला किया, रूसी ड्रोन पोलैंड की हवाई सीमा में घुस गए, और सऊदी अरब ने पाकिस्तान के साथ एक ऐतिहासिक आपसी रक्षा संधि पर हस्ताक्षर किए।

अलग-अलग ये घटनाएँ ही गंभीर होतीं, लेकिन मिलकर ये संकेत देती हैं कि दुनिया अस्थिरता की ओर तेज़ी से बढ़ रही है—जहाँ संप्रभुता, निवारण (deterrence) और मध्यस्थता जैसे पुराने मानदंड लगातार टूट रहे हैं। यह लेख इन संकटों की गहराई, आपसी संबंधों और वैश्विक व्यवस्था पर उनके प्रभावों की पड़ताल करता है।

क़तर में इज़रायल का हमला: युद्धक्षेत्र की नई परिभाषा

9 सितंबर को इज़रायल ने दोहा (क़तर) में मिसाइल हमले किए। इन हमलों में कम से कम छह लोगों की मौत हुई और कई इमारतें क्षतिग्रस्त हुईं। दावा किया गया कि निशाना हमास का नेतृत्व था, जो कथित तौर पर क़तर में सक्रिय था। प्रधानमंत्री बेंजामिन नेतन्याहू ने इस कार्रवाई को “पूर्व-निवारक हमला” बताते हुए कहा कि “कोई सुरक्षित ठिकाना नहीं होगा”।

क़तर, जिसने दशकों से खुद को मध्य पूर्व का एक तटस्थ मध्यस्थ स्थापित किया है, इस हमले से हिल गया। उसने ग़ज़ा संघर्षविराम वार्ताओं में अहम भूमिका निभाई थी और मानवीय सहायता पहुँचाने का केंद्र रहा है। अब इज़रायल ने सीधे क़तर की संप्रभुता का उल्लंघन कर न केवल अरब देशों को नाराज़ किया बल्कि अमेरिका और यूरोप की उन कूटनीतिक कोशिशों को भी कमजोर कर दिया जो दोहा पर भरोसा करती रही हैं।

यह हमला इसलिए भी ख़तरनाक है क्योंकि क़तर में अमेरिका का सबसे बड़ा सैन्य अड्डा है। अमेरिकी अधिकारी भी इस कार्रवाई से हैरान रह गए। इससे यह संकेत गया कि अब कूटनीतिक “सुरक्षित क्षेत्र” भी युद्ध की चपेट से बाहर नहीं हैं।

पोलैंड के ऊपर रूसी ड्रोन: नाटो की अग्निपरीक्षा

इज़रायल के हमले के कुछ घंटों बाद ही यूरोप में नया संकट खड़ा हो गया। 9–10 सितंबर की रात रूस के कम से कम 19 ड्रोन पोलैंड की हवाई सीमा में घुस गए, जब मॉस्को ने यूक्रेन पर व्यापक हवाई हमला किया। पोलैंड ने लड़ाकू विमान तैनात कर कई ड्रोन गिराए। यह पहली बार था जब किसी नाटो सदस्य ने सीधे रूसी संपत्ति पर हमला किया।

यूक्रेनी राष्ट्रपति वोलोदिमिर ज़ेलेंस्की ने आरोप लगाया कि यह रूस की “नाटो की परीक्षा” लेने की सोची-समझी रणनीति थी। खुफ़िया एजेंसियाँ अब भी बँटी हुई हैं कि यह जानबूझकर किया गया या तकनीकी ग़लती से हुआ, लेकिन संदेश साफ़ था—यूक्रेन युद्ध अब यूक्रेन की सीमा से बाहर फैल रहा है।

इस घटना ने नाटो के अनुच्छेद 5 (सामूहिक सुरक्षा) को लेकर भय बढ़ा दिया है। एक छोटी सी ग़लती या दुर्घटना सीधे अमेरिका और यूरोप को रूस के साथ टकराव की ओर धकेल सकती है। इससे यह भी स्पष्ट होता है कि रूस अब लगातार सीमा लांघकर पश्चिमी एकता को परख रहा है, जबकि नाटो देशों में यूक्रेन को समर्थन देने की थकान और घरेलू दबाव बढ़ रहे हैं।

सऊदी–पाकिस्तान रक्षा संधि: खाड़ी में परमाणु साया

17 सितंबर को सऊदी क्राउन प्रिंस मोहम्मद बिन सलमान और पाकिस्तानी प्रधानमंत्री शहबाज़ शरीफ़ ने रियाद में एक आपसी रक्षा समझौते पर हस्ताक्षर किए। इस संधि के तहत दोनों देश किसी भी बाहरी हमले की स्थिति में एक-दूसरे की रक्षा करेंगे।

सऊदी और पाकिस्तान दशकों से सुरक्षा सहयोगी रहे हैं, लेकिन पहली बार इसे औपचारिक रूप दिया गया है। सऊदी को ईरान से ख़तरे का सामना है और उसे अमेरिकी सुरक्षा गारंटी अब उतनी मज़बूत नहीं लगती। पाकिस्तान अपने साथ परमाणु हथियारों का विकल्प लाता है। भले ही संधि में परमाणु सहयोग का ज़िक्र न हो, लेकिन इसे “परमाणु छाते” की दिशा में पहला कदम माना जा रहा है।

इससे दक्षिण एशिया में भी नई जटिलताएँ खड़ी होती हैं। अगर भारत और पाकिस्तान के बीच टकराव होता है, तो क्या सऊदी इसमें खिंच आएगा? क्या खाड़ी की प्रतिद्वंद्विताएँ अब परमाणु परछाईं में घिर जाएँगी? विशेषज्ञ मानते हैं कि यह संधि अभी प्रतीकात्मक ज़्यादा है, लेकिन प्रतीक भी रणनीतिक समीकरण बदल देते हैं।

परस्पर संबंध: बदलती बहुध्रुवीय दुनिया

इन घटनाओं को अलग-अलग नहीं देखा जा सकता। ये सब मिलकर यह दिखाती हैं कि अमेरिका-नेतृत्व वाली एकध्रुवीय व्यवस्था अब टूट रही है और एक बहुध्रुवीय (multipolar) विश्व उभर रहा है जहाँ मध्य शक्तियाँ भी आक्रामक रुख़ अपनाने लगी हैं।

-

क़तर में इज़रायल का हमला बताता है कि युद्धक्षेत्र अब सीमाओं तक सीमित नहीं है।

-

पोलैंड में रूसी ड्रोन यह दिखाते हैं कि यूरोप में हर दिन टकराव का ख़तरा मंडरा रहा है।

-

सऊदी–पाकिस्तान संधि यह इशारा देती है कि नई सुरक्षा व्यवस्थाएँ पुराने गठबंधनों को दरकिनार कर रही हैं।

ये सभी घटनाएँ उस वैश्विक माहौल का हिस्सा हैं जहाँ यूक्रेन और ग़ज़ा में युद्ध जारी हैं, ऊर्जा और खाद्य आपूर्ति संकटग्रस्त हैं, और राष्ट्रवाद तथा अधिनायकवाद बढ़ रहे हैं।

निहितार्थ: संयम या टकराव?

इन “लांघी गई सीमाओं” के तीन बड़े निहितार्थ हैं:

-

कूटनीतिक मध्यस्थता का क्षरण – क़तर की मध्यस्थ भूमिका अब कमज़ोर हो सकती है।

-

तनाव की सामान्यीकरण – सीमा उल्लंघन और हमले अब “नियम” बनते जा रहे हैं, जिससे दुर्घटना का जोखिम बढ़ रहा है।

-

नई सुरक्षा संरचनाएँ – सऊदी–पाकिस्तान जैसी संधियाँ समानांतर रक्षा गुट बना सकती हैं।

फिर भी, पूरी तरह अंधकारमय तस्वीर नहीं है। पोलैंड वाले मामले में नाटो की संयमित प्रतिक्रिया और क़तर का मानवीय मध्यस्थता जारी रखना यह दिखाता है कि संयम अभी भी प्राथमिकता है। संयुक्त राष्ट्र महासभा नेताओं के लिए संवाद का मंच बना हुआ है, भले ही उसकी प्रभावशीलता सीमित हो।

सितंबर 2025 का यह मोड़ साफ़ करता है कि 20वीं सदी के संस्थान और नियम अब पर्याप्त नहीं हैं। भविष्य इस पर निर्भर करेगा कि बड़ी शक्तियाँ सहयोग का रास्ता चुनती हैं या टकराव का।

Trump, the WTO, and the Perils of a Fractured Multipolar World

In 2025, global stability has been tested on multiple fronts—from escalating wars to shifting alliances—but few events have been as destabilizing as U.S. President Donald Trump’s singular dismantling of the World Trade Organization (WTO). For decades, the WTO was the anchor of the global trading system, enforcing rules, mediating disputes, and offering smaller economies a sense of protection against the whims of powerful states. By undermining it, Washington has not only weakened a key international institution but has accelerated the fragmentation of the global order.

Trump’s actions on the domestic front have only added to the volatility. With sweeping tariffs, deregulation campaigns, and an “America First” economic agenda that prioritizes unilateral action over collective frameworks, the U.S. is sending a clear message: it is willing to bypass the international system it once championed.

The WTO’s Collapse: End of an Era

The WTO has long faced criticism for being slow, overly bureaucratic, and at times ill-equipped to deal with 21st-century challenges such as digital trade, climate-linked commerce, and supply chain security. Yet, its existence provided predictability and a rules-based framework that restrained trade wars.

Trump’s decision to effectively dismantle the organization—by blocking appointments, refusing compliance with rulings, and launching sweeping tariffs that defy WTO guidelines—has rendered it toothless. For many nations, the collapse signals a return to the 1930s-style trade blocs, where power rather than principle determines outcomes.

This collapse has emboldened regional groupings such as BRICS+ and driven bilateral trade deals, often on unequal terms. Developing nations that once relied on WTO mechanisms for fair arbitration now find themselves vulnerable to coercion by economic giants.

A Multipolar World—By Default, Not Design

The weakening of global institutions has coincided with the rise of multipolarity. China, India, the EU, Russia, and regional coalitions are all asserting themselves more forcefully, filling the vacuum left by American retrenchment. In theory, a multipolar world need not be inherently unstable. Balanced power among several players could allow for a more inclusive system where no single state dominates.

However, what is unfolding is a disorderly shift. Instead of coordinated reform, multipolarity is emerging through conflict, unilateralism, and economic coercion. Without mechanisms of trust, dialogue, and arbitration, the new order risks being one of confrontation rather than cooperation.

The Case for Dialogue and Cooperation

There is still a path to a less disruptive transition. Multipolarity can be managed if major powers recognize the need for shared institutions—even if reformed ones. A reimagined global trade body, designed for modern realities, could restore predictability while allowing space for regional diversity. Enhanced dialogue through forums like the G20 and UN can help prevent rivalries from hardening into permanent fractures.

Moreover, cooperation on pressing global challenges—climate change, pandemics, cyber threats, and financial stability—remains possible only through multilateral engagement. The alternative is a fragmented system where crises are met with narrow, short-term responses, amplifying instability.

Rising Tensions, Shrinking Options

The greatest obstacle to such cooperation is the escalating cycle of tensions. From Ukraine to Gaza, from tariffs to technology bans, states are increasingly turning inward or weaponizing interdependence. Each move away from dialogue reinforces distrust, making it harder to build the cooperative frameworks that multipolarity requires.

The paradox is clear: the world is moving toward multipolarity regardless of intention, but whether that future is stable or volatile depends on the choices made now. More dialogue and cooperation offer a chance for a softer landing. Continued unilateralism, however, risks ensuring that the collapse of the WTO is remembered not just as the end of an institution, but as the beginning of a fractured era.

ट्रंप, WTO और खंडित बहुध्रुवीय विश्व के खतरे

2025 में वैश्विक स्थिरता कई मोर्चों पर परखी गई है—बढ़ते युद्धों से लेकर बदलते गठबंधनों तक। लेकिन कुछ ही घटनाएँ उतनी अस्थिर करने वाली रही हैं जितनी अमेरिकी राष्ट्रपति डोनाल्ड ट्रंप द्वारा विश्व व्यापार संगठन (WTO) को लगभग ध्वस्त कर देना। दशकों से WTO वैश्विक व्यापार प्रणाली की धुरी रहा है, नियम लागू करता रहा, विवादों का समाधान करता रहा, और छोटे–मझोले देशों को बड़ी शक्तियों की मनमानी से सुरक्षा का एहसास दिलाता रहा। इसके विघटन ने न केवल एक प्रमुख अंतरराष्ट्रीय संस्था को कमजोर किया है, बल्कि वैश्विक व्यवस्था के विखंडन को भी तेज़ कर दिया है।

ट्रंप की घरेलू नीतियों ने इस अस्थिरता को और गहरा दिया है। व्यापक टैरिफ़, विनियमन–उन्मूलन अभियानों और “अमेरिका फ़र्स्ट” आर्थिक एजेंडे के साथ, अमेरिका यह स्पष्ट संकेत दे रहा है कि वह उस अंतरराष्ट्रीय प्रणाली को दरकिनार करने को तैयार है, जिसका कभी वह संरक्षक हुआ करता था।

WTO का पतन: एक युग का अंत

WTO की आलोचना लंबे समय से होती रही है कि वह धीमा है, नौकरशाही में जकड़ा हुआ है, और डिजिटल व्यापार, जलवायु–संबद्ध वाणिज्य या आपूर्ति श्रृंखला सुरक्षा जैसी 21वीं सदी की चुनौतियों से निपटने में सक्षम नहीं। फिर भी, उसका अस्तित्व पूर्वानुमान और नियम–आधारित ढाँचा देता था, जिसने बड़े पैमाने पर व्यापार युद्धों को रोके रखा।

ट्रंप के कदम—न्यायाधीश नियुक्तियों को रोकना, फैसलों का पालन न करना, और WTO नियमों की अवहेलना करते हुए भारी टैरिफ़ लगाना—ने संगठन को लगभग निष्प्रभावी बना दिया है। बहुतों के लिए यह संकेत है कि दुनिया अब 1930 के दशक की तरह क्षेत्रीय व्यापार गुटों की ओर लौट रही है, जहाँ सिद्धांत नहीं बल्कि शक्ति का बोलबाला होता है।

इस पतन ने BRICS+ जैसे क्षेत्रीय गुटों को और साहस दिया है और असमान द्विपक्षीय समझौतों को जन्म दिया है। विकासशील देश, जो पहले निष्पक्ष मध्यस्थता के लिए WTO पर भरोसा करते थे, अब आर्थिक दिग्गजों की मनमानी के सामने असुरक्षित महसूस कर रहे हैं।

बहुध्रुवीय विश्व—डिज़ाइन से नहीं, मजबूरी से

वैश्विक संस्थानों के कमजोर होने के साथ ही बहुध्रुवीयता (multipolarity) का उदय हुआ है। चीन, भारत, यूरोपीय संघ, रूस और क्षेत्रीय गठबंधन अब अधिक आक्रामक ढंग से अपनी स्थिति मजबूत कर रहे हैं, उस रिक्त स्थान को भरने के लिए जो अमेरिकी संकोच से बना है।

सिद्धांततः, बहुध्रुवीय विश्व अस्थिर होना ज़रूरी नहीं है। यदि कई शक्तियों के बीच संतुलन हो तो यह अधिक समावेशी प्रणाली बना सकता है, जहाँ कोई एक राज्य हावी न हो।

लेकिन जो वास्तविकता बन रही है, वह अव्यवस्थित है। समन्वित सुधारों की बजाय, बहुध्रुवीयता संघर्ष, एकतरफ़ावाद और आर्थिक दबाव के जरिये आकार ले रही है। बिना विश्वास और मध्यस्थता की प्रणालियों के, नया विश्व–क्रम टकराव की ओर झुकता दिख रहा है।

संवाद और सहयोग का मामला

फिर भी, एक कम विघटनकारी रास्ता अब भी मौजूद है। यदि प्रमुख शक्तियाँ साझा संस्थाओं की आवश्यकता स्वीकार करें—भले वे नए सिरे से क्यों न हों—तो बहुध्रुवीयता को संभालना संभव है। आधुनिक वास्तविकताओं के अनुरूप पुनः कल्पित एक वैश्विक व्यापार निकाय पूर्वानुमेयता वापस ला सकता है और क्षेत्रीय विविधता को जगह दे सकता है।

G20 और संयुक्त राष्ट्र जैसे मंचों पर गहन संवाद प्रतिद्वंद्विताओं को स्थायी दरार बनने से रोक सकते हैं। जलवायु परिवर्तन, महामारी, साइबर ख़तरे और वित्तीय स्थिरता जैसी चुनौतियाँ केवल बहुपक्षीय सहयोग से ही हल हो सकती हैं। वैकल्पिक व्यवस्था—खंडित, अल्पकालिक और संकीर्ण दृष्टिकोण वाली—अस्थिरता को और बढ़ाएगी।

बढ़ता तनाव, घटते विकल्प

सबसे बड़ी बाधा बढ़ते तनावों का चक्र है। यूक्रेन से गाज़ा तक, टैरिफ़ से लेकर प्रौद्योगिकी प्रतिबंधों तक—राष्ट्र लगातार भीतर की ओर सिमट रहे हैं या आपसी निर्भरता को हथियार बना रहे हैं। संवाद से हर दूरी अविश्वास को और मजबूत करती है, जिससे बहुध्रुवीयता के लिए ज़रूरी सहयोगी ढाँचा बनाना और कठिन हो जाता है।

विरोधाभास स्पष्ट है: दुनिया बहुध्रुवीयता की ओर तो बढ़ ही रही है, लेकिन यह भविष्य स्थिर होगा या अस्थिर, यह आज किए गए विकल्पों पर निर्भर करेगा। अधिक संवाद और सहयोग एक मुलायम अवतरण का अवसर देते हैं। जबकि निरंतर एकतरफ़ावाद यह सुनिश्चित करेगा कि WTO का पतन केवल एक संस्था का अंत न होकर, एक खंडित युग की शुरुआत के रूप में याद किया जाए।