From the Chinese perspective, the 1962 Sino-Indian War is typically framed as a defensive counterattack triggered by India’s forward policy and perceived territorial encroachment. Here’s a detailed look at how China views the conflict:

1. Historical Context: Chinese Claims

-

China maintains that both Aksai Chin (in the west) and parts of Arunachal Pradesh (then NEFA, in the east) have historically been Chinese territory.

-

In particular, Aksai Chin was crucial for China as it linked Tibet and Xinjiang through the G219 highway, constructed in the 1950s. India protested this, but China viewed the road as vital to national integration and internal security.

2. India’s Forward Policy

-

Chinese narratives assert that India adopted an aggressive forward policy, placing outposts beyond its own claimed boundaries, effectively intruding into territory China saw as its own.

-

Mao Zedong and other Chinese leaders reportedly saw this as provocative and expansionist behavior on India’s part.

3. Tibet and the Dalai Lama

-

The 1959 Tibetan uprising and the Dalai Lama’s flight to India severely damaged Sino-Indian relations.

-

From China’s point of view, India’s sheltering of the Dalai Lama was seen as interference in its internal affairs and a direct challenge to Chinese sovereignty over Tibet.

4. Perception of Nehru’s Ambitions

-

Chinese officials believed Nehru had hegemonic aspirations in Asia, imagining India as a civilizational leader of the non-aligned world.

-

The "Panchsheel" policy of peaceful coexistence was seen by some in China as Indian rhetoric that masked real territorial ambitions.

5. The 1962 War: A Limited, Punitive Campaign

-

China claims it launched a limited military operation to "teach India a lesson" and to reassert the Line of Actual Control (LAC).

-

From the Chinese perspective, the war was a decisive but restrained show of strength: they advanced quickly, inflicted losses, and then voluntarily withdrew to pre-war positions — signaling they had no long-term territorial ambitions in the eastern sector.

6. Aftermath and Diplomatic Messaging

-

Chinese officials presented the unilateral ceasefire and withdrawal as evidence of China's peaceful intent.

-

Beijing also emphasized that the war was not a beginning of long-term hostility, but a corrective action due to what they perceived as India's refusal to negotiate.

7. Present-Day Narratives

-

In official Chinese discourse, the war is rarely emphasized in public media or textbooks — it's not glorified the way other conflicts (like the Korean War) are.

-

However, when referenced, it’s portrayed as a legitimate response to Indian provocation and as an assertion of China’s territorial rights.

-

China continues to oppose India’s claims over Arunachal Pradesh, calling it “South Tibet.”

Summary of the Chinese View:

The 1962 war was a defensive measure, necessitated by India’s encroachment and political duplicity over the border issue and Tibet. China asserts it acted reluctantly but decisively, and then withdrew out of goodwill — demonstrating it sought peace, not conquest.

The Indian perspective on the 1962 India-China War is very different from the Chinese view. India sees itself as the victim of unprovoked aggression by a more powerful neighbor that betrayed a policy of peaceful coexistence and violated established norms. Here's a comprehensive breakdown:

🇮🇳 1. Historical Context and Borders

-

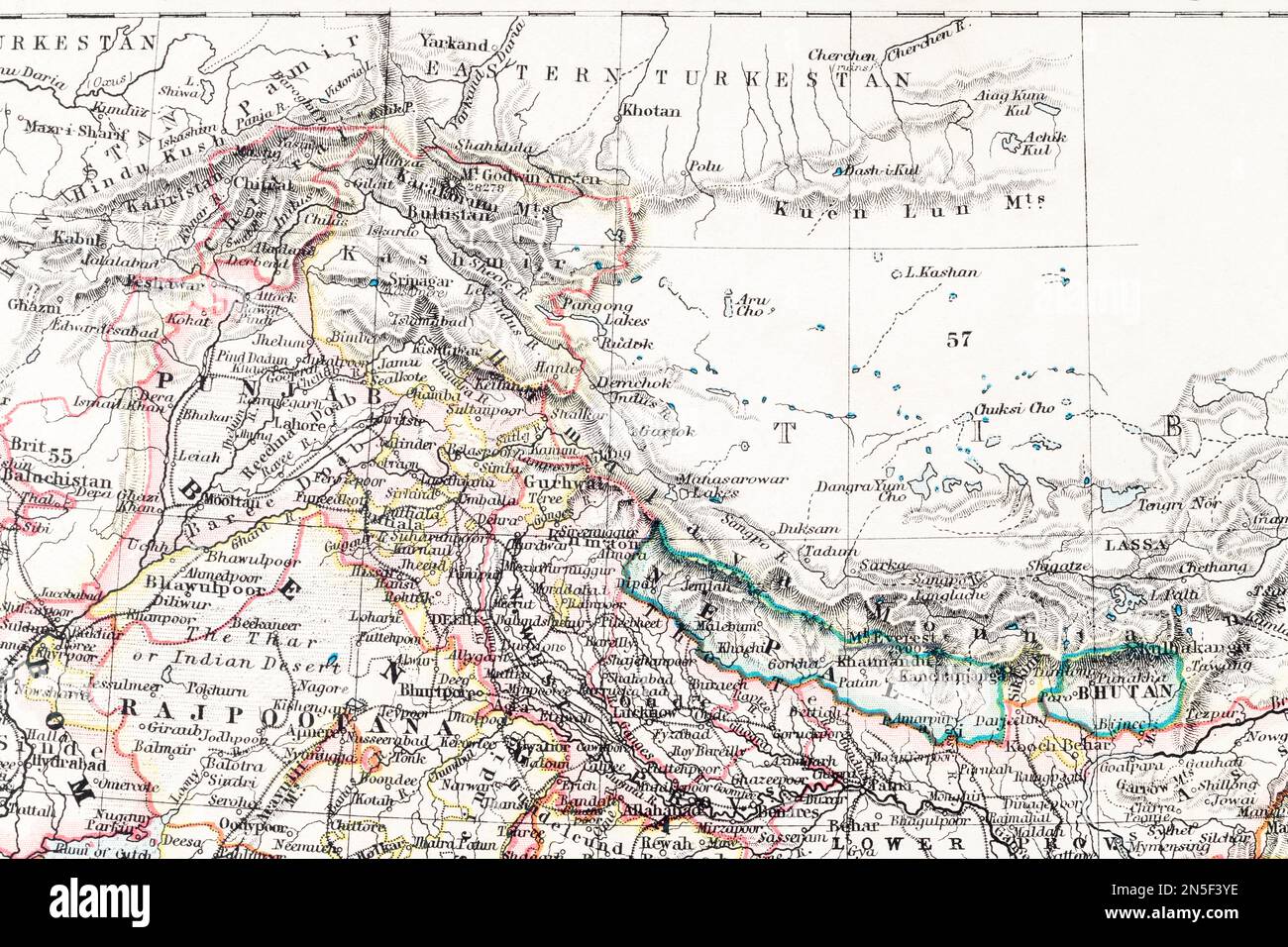

India inherited colonial-era boundaries after independence in 1947, particularly the McMahon Line in the eastern sector (Arunachal Pradesh/NEFA), which the British had negotiated with Tibet in 1914.

-

India considers Aksai Chin an integral part of the Ladakh region of Jammu and Kashmir.

-

India argues that China had no historical claim over Aksai Chin until after it occupied Tibet in 1950.

🇮🇳 2. Betrayal of Panchsheel and the “Hindi-Chini Bhai-Bhai” Era

-

India had strongly supported the People’s Republic of China’s entry into the UN and recognized Chinese sovereignty over Tibet.

-

The Panchsheel Agreement (1954) was seen as a high point of India-China friendship.

-

The war was perceived in India as a betrayal of that spirit of brotherhood (“Hindi-Chini Bhai Bhai”).

🇮🇳 3. China's Road in Aksai Chin: A Surprise

-

In the late 1950s, India discovered that China had built a road through Aksai Chin, which India considered its territory.

-

India viewed this as a covert invasion, carried out without diplomatic notification.

🇮🇳 4. Tibet and the Dalai Lama

-

India believes it had a moral and humanitarian duty to offer asylum to the Dalai Lama in 1959 after the Chinese crackdown in Tibet.

-

India does not see this as political interference, but China interpreted it as a hostile act, worsening tensions.

🇮🇳 5. India’s Forward Policy: Defensive, Not Aggressive

-

India maintains that its Forward Policy was designed to reassert control over its own territory, not to provoke China.

-

The military outposts India set up were within what it considered its undisputed boundaries.

🇮🇳 6. The War: A Surprise Attack

-

On October 20, 1962, China launched a coordinated attack on Indian positions in both the eastern and western sectors.

-

India believes the attack was premeditated, not a reaction to Indian movements.

-

The Indian army was underprepared and outgunned, leading to a humiliating defeat, especially in Arunachal Pradesh (NEFA), where China advanced deep before withdrawing.

🇮🇳 7. Unilateral Chinese Withdrawal: Strategic, Not Peaceful

-

China’s withdrawal is seen in India as tactical, not generous — a move made only after it had made its point militarily and diplomatically.

-

India believes that China’s goal was to redraw the Line of Actual Control (LAC) unilaterally and assert dominance.

🇮🇳 8. Nehru’s Leadership and National Trauma

-

The war shattered India’s self-image and global non-aligned stature.

-

PM Jawaharlal Nehru’s government was heavily criticized for misjudging China’s intentions and leaving the army ill-equipped.

-

The defeat led to massive defense reforms in India and shaped long-term suspicion of China.

🇮🇳 9. Continuing Dispute: No Closure

-

India continues to claim Aksai Chin as illegally occupied by China.

-

China claims Arunachal Pradesh as “South Tibet,” which India firmly rejects.

-

The LAC remains undefined, leading to regular standoffs, like the 2020 Galwan Valley clash.

Summary of the Indian View:

India sees the 1962 war as a deliberate Chinese invasion across a historically agreed boundary, launched after India’s peaceful overtures. The war was a rude awakening about the nature of Chinese intentions and has shaped Indian strategic thinking ever since.

The history of the India-China border over the last 1000 years is complex, largely because for much of that time, there were no fixed national borders in the modern sense, especially in the high Himalayas. What existed were zones of influence, local kingdoms, and tributary relationships. The idea of a well-demarcated border is a colonial and post-colonial development.

Here is a historical overview broken down into major periods:

🌄 1. Pre-13th Century: Ancient and Classical Era

-

India and China rarely shared direct borders. The vast Himalayas and Tibetan Plateau acted as a buffer.

-

Tibet, an independent cultural and political entity, served as the geographical and civilizational intermediary.

-

Contact between the two civilizations occurred via:

-

Trade routes (Silk Road, trans-Himalayan paths)

-

Pilgrimage (Buddhist monks traveling between Nalanda and Chinese centers of learning)

-

Diplomacy, but rarely direct political conflict.

-

🏯 2. 13th–17th Century: Mongol and Ming Periods

-

Tibet was influenced by Mongol and later Chinese (Ming) dynasties, but remained largely autonomous.

-

India’s northern regions were under the Delhi Sultanate and later the Mughal Empire.

-

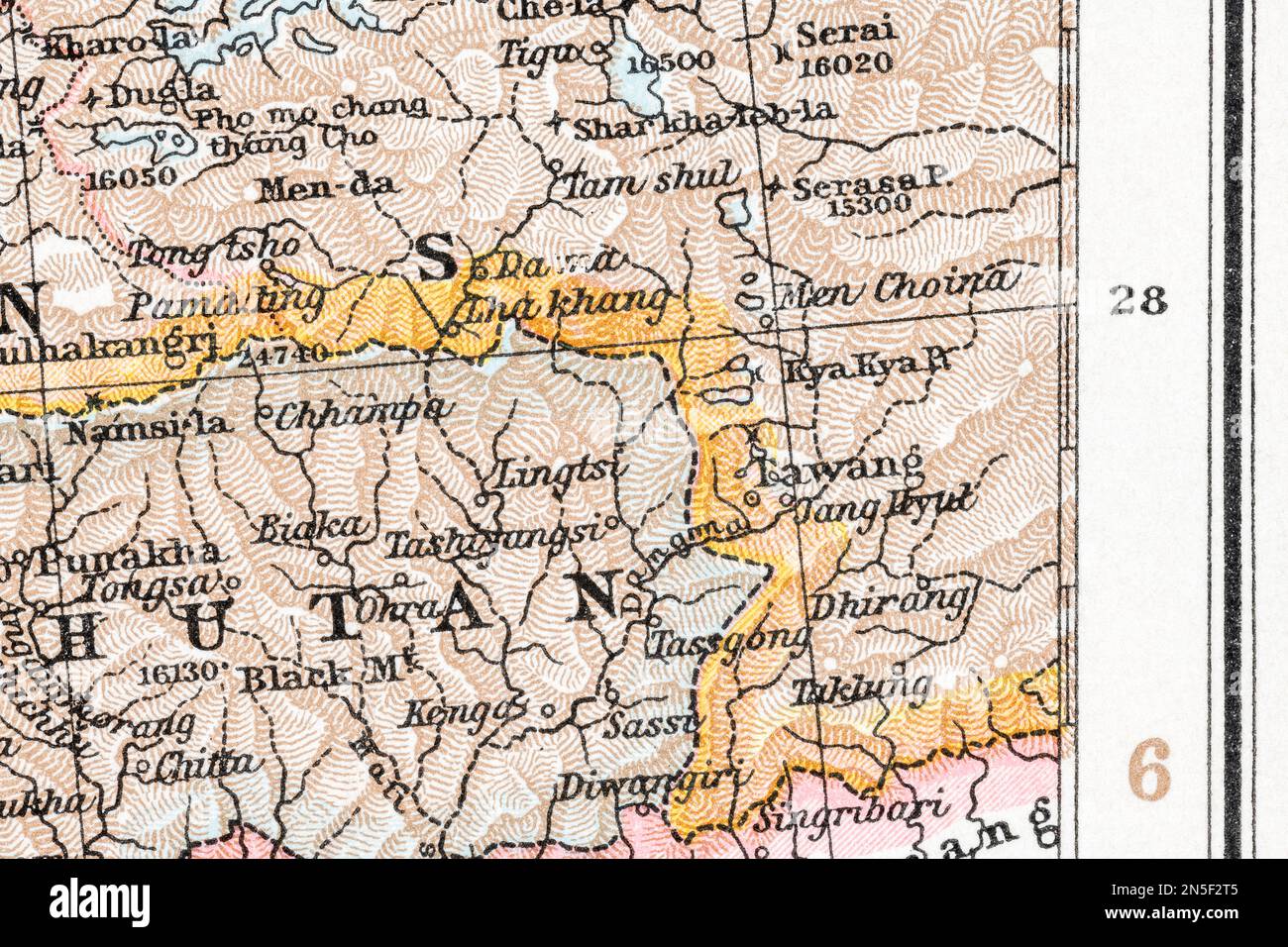

Ladakh, Sikkim, and Bhutan were Himalayan kingdoms with varying degrees of autonomy.

-

There was no direct India-China border — Tibet was not part of China, and India’s reach didn’t extend into Tibet.

🏔️ 3. 17th–18th Century: Qing Expansion and Himalayan Kingdoms

-

The Qing dynasty (1644–1912) began to assert stronger control over Tibet by the early 18th century.

-

Ladakh and Tibet fought wars (e.g., the 1679–1684 Tibet–Ladakh–Mughal War).

-

The Treaty of Tingmosgang (1684) settled boundaries between Ladakh and Tibet, with Mughal mediation — this forms one of the few pre-modern references to borders in the western sector.

-

The British East India Company started engaging with Himalayan states like Sikkim and Bhutan by the late 1700s.

🧭 4. 19th Century: British India and the Creation of Borders

-

This was the crucial period for modern borders.

-

The British, concerned about Russian expansion, pushed northward, seeking to secure their Indian empire’s frontier.

Key Developments:

-

McCartney–MacDonald Line (1899): A British proposal to China demarcating Aksai Chin as Chinese — not formally accepted.

-

Simla Convention (1914): Britain negotiated with Tibet to define borders.

-

The McMahon Line was drawn, defining the boundary between Tibet and British India (modern Arunachal Pradesh).

-

China did not sign, rejecting Tibetan autonomy, so it never recognized the McMahon Line.

-

-

Despite Chinese rejection, British India began administering up to the McMahon Line.

🧳 5. Early 20th Century: Fall of Empires and Changing Claims

-

1911–49: The fall of Qing China, rise of Republican China, and eventual Communist revolution created confusion over borders.

-

Tibet functioned autonomously from 1912 to 1950, signing treaties with the British and operating its own government.

-

India gained independence in 1947, inheriting British-administered borders.

🚨 6. 1950–1962: PRC Takes Over Tibet and the Border Dispute Begins

-

In 1950, China invaded Tibet and integrated it into the PRC.

-

India recognized Chinese sovereignty over Tibet in 1954, hoping for good relations.

-

But the boundary issue flared up because:

-

China started building a road through Aksai Chin (1956–57), which India discovered later.

-

China rejected the McMahon Line and began claiming parts of NEFA (Arunachal Pradesh).

-

-

All this led to rising tensions and culminated in the 1962 Sino-Indian War.

📍 7. Post-1962: Stalemate and LAC

-

The Line of Actual Control (LAC) became the de facto border, but remains disputed and undefined in many sectors.

-

China controls Aksai Chin, India controls Arunachal Pradesh.

-

Skirmishes have continued, most notably:

-

Sumdorong Chu (1987)

-

Doklam standoff (2017)

-

Galwan Valley clash (2020)

-

🧭 Summary Timeline:

| Era | Status |

|---|---|

| Pre-1700s | No India-China border; Tibet as buffer zone |

| 1700s | Qing China begins influence in Tibet; India under Mughals/British |

| 1800s | British define borders with Tibet (not China) |

| 1914 | McMahon Line drawn at Simla Convention |

| 1950 | PRC annexes Tibet; border disputes begin |

| 1962 | War leads to current Line of Actual Control |

| 2020s | Border remains contested; flashpoints persist |

Here's a rich, map-based visual along with a detailed timeline and sector-by-sector comparison of the India–China border's evolution:

🕰️ 1. Map-Based Historical Timeline (Last 1000 Years)

-

Pre‑1700s: No formal India–China border existed. Tibet acted as an autonomous buffer state. Trade and cultural routes traversed the Himalayas, but political control was local or regional.

-

17th–18th Centuries: The Qing dynasty gradually extended its influence over Tibet. Himalayan kingdoms—like Ladakh and Sikkim—existed under variable suzerainty. The Tibetan–Ladakhi war (1679–1684) ended with the Treaty of Tingmosgang, one of few pre-colonial border settlements.

-

19th Century: With the British Raj's northward expansion, three proposed border lines arose in Aksai Chin:

-

Ardagh–Johnson Line (1865/1897): placed Aksai Chin within British India and later adopted by independent India (alamy.com, en.wikipedia.org).

-

Macartney–MacDonald Line (1899): proposed to China as a compromise; remained unacknowledged (en.wikipedia.org).

-

McMahon Line (1914, Simla Convention): drawn between British India and Tibet; China did not ratify and contests its validity (en.wikipedia.org).

-

-

Early 20th Century: After the Qing fell, China was unstable; Tibet functioned de facto independently. Britain administered the McMahon Line region post‑1914.

🌄 2. Declared Boundaries in Three Sectors

Western (Ladakh–Aksai Chin)

-

Johnson Line: Indian basis for control over Aksai Chin (en.wikipedia.org).

-

China builds G219 highway through Aksai Chin in the 1950s; refuses India's territorial claim → sparks 1962 conflict.

-

Post-war: China retains control of approximately 38,000 km² of Aksai Chin (crisisgroup.org).

-

LAC established after 1962, not matching either claimed lines (en.wikipedia.org).

Central (Uttarakhand & Himachal Pradesh)

-

Mostly undisputed, with a customary frontier based on traditional usage. No formal treaty ever. Border demarcation grounded in local administrative practices .

Eastern (Arunachal Pradesh/NEFA & Sikkim)

-

India follows the McMahon Line, claiming the territory as Arunachal Pradesh.

-

China regards it as "South Tibet", rejecting the McMahon Line’s legal validity (en.wikipedia.org).

-

Several conflicts: 1962 war, 1967 Nathu La and Cho La, 1986–87 Sumdorong Chu, recent 2020–22 skirmishes at Tawang sector (iai.it).

📅 3. Key Milestones Since 1947

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1947‑50 | India inherits British-administered claims; PRC establishes control over Tibet (1950); India recognizes Tibet as part of China (1954) . |

| 1956–57 | China constructs the G219 road through Aksai Chin. India confirms the intrusion later. |

| 1959–1960 | Zhou Enlai letters identify Chinese claim line; negotiations fail . |

| 1962 | Sino‑Indian War sees China advance into NEFA and Aksai Chin, then withdraws unilaterally to LAC . |

| 1963 | Pakistan cedes Trans‑Karakoram Tract to China . |

| 1967, 1986–87, 2017 | Skirmishes in eastern sector: Nathu La, Cho La, Sumdorong Chu . |

| 1993–96 | Confidence-building agreements and protocols to respect LAC without formal demarcation . |

| 2020 | Galwan Valley clash kills 20 Indian and 4 Chinese soldiers; India increases deployments and infrastructure . |

| 2022–24 | Continued minor scuffles; recent disengagement talks in eastern Ladakh; transfer of hydropower and infrastructure works in Arunachal Pradesh . |

🧭 4. Sector-by-Sector Comparison

| Sector | India’s Position | China’s Position | Current Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Western | Aksai Chin part of Ladakh (Johnson Line) | Claims per 1956/60 lines; control since 1962 | China controls; LAC stands |

| Central | Border based on longstanding administrative usage | No challenge; implicit acceptance | Undisputed LAC |

| Eastern | McMahon Line defines Arunachal Pradesh | Rejects McMahon; claims “South Tibet” | China claims but not fully controlled; LAC volatile |

✅ In Summary

From medieval buffer zones to colonial-era treaties and modern strategic posturing, the India–China border evolved through:

-

Buffer state era (Tibet)

-

Qing influence & Himalayan polity dynamics

-

British-drafted lines (Johnson, Macartney–MacDonald, McMahon)

-

PRC claim consolidation post-1950 leading to 1962 war

-

Establishment of an ill-defined LAC, with recurrent tensions and contestations in key sectors

Diplomatic efforts between India and China to resolve their long-standing border dispute have spanned over six decades, involving dozens of meetings, confidence-building agreements, and attempts at demarcating or managing the Line of Actual Control (LAC). However, despite some temporary breakthroughs, no final settlement has yet been reached.

Here is an in-depth exploration of the key diplomatic phases, major agreements, and current status:

🕊️ 1. Early Diplomatic Exchanges (1950s–1962)

-

1954 Panchsheel Agreement:

-

India recognized Chinese sovereignty over Tibet, hoping for mutual respect of boundaries.

-

The phrase "Hindi-Chini Bhai Bhai" symbolized the optimistic spirit.

-

-

1959–1960 Border Talks:

-

After the Dalai Lama's escape and border skirmishes, PM Nehru and Premier Zhou Enlai exchanged letters.

-

Zhou proposed status quo-based compromise (China keeps Aksai Chin, India keeps NEFA), but India rejected it.

-

-

1962 War ended direct negotiations and set back ties for decades.

📃 2. Post-War Freeze and Gradual Thaw (1963–1988)

-

No formal diplomatic engagement occurred for over 15 years.

-

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, relations improved slightly through trade delegations and ambassador-level contacts.

-

1988: Rajiv Gandhi's Visit to China was a landmark thaw. India and China agreed to set aside the boundary issue and normalize ties.

🤝 3. Confidence Building Measures (CBMs) and Agreements (1993–2005)

🔹 1993: Agreement on the Maintenance of Peace and Tranquility along the LAC

-

Recognized the LAC as the de facto border (not legally delimited).

-

Both sides committed to respecting the status quo and avoiding escalation.

🔹 1996: CBM Agreement

-

Banned use of firearms within 2 km of the LAC.

-

Limited troop numbers and established procedures for patrols and communication.

🔹 2003: Joint Declaration & Special Representatives Mechanism

-

PM Atal Bihari Vajpayee visited Beijing.

-

Both sides appointed Special Representatives (SRs) to explore a political framework for boundary settlement.

🔹 2005: Agreement on Political Parameters and Guiding Principles

-

Laid out the framework for eventual resolution:

-

Border should not disturb settled populations (relevant to Arunachal).

-

Both sides would show flexibility and "mutual adjustments."

-

-

This was seen as a major diplomatic achievement, though not followed by concrete demarcation.

⚠️ 4. Stalemates and Setbacks (2006–2017)

-

Talks continued under SRs but progress stalled.

-

China intensified claims over Arunachal Pradesh, especially Tawang, and began opposing Indian infrastructure.

-

Border incursions increased (Depsang 2013, Chumar 2014).

-

2017: Doklam Standoff:

-

India opposed China’s road-building in disputed Bhutanese territory.

-

73-day standoff resolved via diplomatic disengagement, seen as a test case for CBMs.

-

💥 5. Galwan and the Breakdown of Trust (2020–Present)

🔹 2020: Galwan Valley Clash

-

First deaths in decades on LAC (20 Indian soldiers, 4 Chinese officially).

-

Massive military buildup followed on both sides.

-

Diplomatic protocols were severely undermined.

🔹 Post-Galwan Diplomacy:

-

Over 20 rounds of Corps Commander-level military talks have taken place.

-

Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination (WMCC) meetings at diplomatic level continue.

-

Some disengagement in areas like Pangong Tso, Galwan, and Gogra-Hot Springs, but standoffs remain in Depsang and Demchok.

🧭 6. Current Status and Strategic Diplomacy

🔸 India’s Position:

-

Restoration of pre-April 2020 status quo is a precondition for full normalization.

-

India links boundary resolution to the broader relationship — “peace and tranquility is a prerequisite.”

🔸 China’s Position:

-

China prefers to decouple the border issue from overall ties — continue trade and diplomacy while keeping LAC unsettled.

-

China’s maps continue to claim Arunachal Pradesh as South Tibet, and Aksai Chin as fully Chinese.

📌 Key Diplomatic Institutions and Formats Today:

| Format | Role |

|---|---|

| Special Representatives (SR) Talks | Strategic dialogue on boundary settlement framework |

| Corps Commander-Level Talks | Tactical discussions on troop disengagement and buffer zones |

| WMCC (Working Mechanism for Consultation & Coordination) | Diplomatic coordination and de-escalation |

| NSA Meetings / SCO / BRICS Summits | Multilateral platforms where side discussions occur |

✍️ Summary

India and China have signed multiple agreements to manage, but not resolve, the border. While diplomatic mechanisms exist, true resolution remains elusive due to strategic mistrust, divergent priorities, and asymmetric perceptions of history.

Here is a proposed roadmap to resolve the India-China border issue — one that balances realism, sovereignty, national pride, and long-term strategic stability. It follows a phased, trust-building approach that could culminate in a formal boundary agreement, if both sides show political will.

🛣️ ROADMAP TO RESOLUTION: INDIA–CHINA BORDER DISPUTE

🔹 Phase 1: Freeze the Conflict and Restore Trust (0–2 years)

✅ Actions:

-

Full disengagement in all friction points, including Depsang and Demchok.

-

Reaffirm and publicly recommit to all existing CBMs (1993, 1996, 2005).

-

Establish mutual buffer zones monitored by joint patrol mechanisms or third-party satellite verification.

-

Expand hotlines and real-time communication at military and diplomatic levels.

-

Ban construction of new military infrastructure within 5–10 km of LAC.

🔑 Outcome:

-

De-escalation of current crisis.

-

Restoration of military and diplomatic credibility and confidence.

🔹 Phase 2: Define the Line of Actual Control (2–5 years)

✅ Actions:

-

Both countries exchange maps of the LAC (China has resisted this).

-

Bilateral surveys with GPS coordinates to establish mutual understanding of patrol limits.

-

Codify the LAC as a working boundary, without prejudice to final claims.

-

Hold local commander-level deconfliction drills to avoid accidental face-offs.

🔑 Outcome:

-

A clearly defined, jointly mapped LAC to prevent misperceptions.

-

Institutional memory created for future negotiations.

🔹 Phase 3: Sector-Wise Resolution and Trade-Offs (5–10 years)

This phase addresses the substantive dispute — with political negotiation and strategic trade-offs.

🌍 Western Sector (Aksai Chin – Ladakh):

-

India may accept China’s control over Aksai Chin de facto with nominal recognition, in exchange for permanent settlement and security guarantees.

-

China may grant overland transit rights (e.g., through Aksai Chin) for trade/pilgrimage, monitored by both sides.

🌄 Eastern Sector (Arunachal Pradesh):

-

India retains sovereignty over Arunachal Pradesh, particularly Tawang.

-

China may drop claim to South Tibet in exchange for economic and cultural access.

-

Establish cross-border economic zones and shared religious pilgrimage corridors (e.g., to Tawang monastery, akin to Kailash–Mansarovar).

🧭 Central Sector:

-

Officially demarcate the boundary based on current peaceful status quo.

🔑 Outcome:

-

Political settlement of the boundary based on strategic compromise.

-

Each side keeps what it controls, with mutual face-saving narrative and some confidence-building gestures.

🔹 Phase 4: Legal Settlement and Treaty (10+ years)

✅ Actions:

-

Draft a Formal Boundary Agreement, including:

-

Demarcated border on official maps

-

Border security protocols

-

Mechanism for joint dispute resolution

-

-

Sign a Treaty of Peaceful Coexistence and Border Friendship.

-

Encourage public narratives emphasizing mutual benefit, historical closure, and regional leadership.

🔑 Outcome:

-

Permanent resolution of the border dispute.

-

India-China relations shift from rivalry to managed competition or even strategic cooperation.

🧠 Strategic Rationale

| Factor | Benefit |

|---|---|

| Security | Reduces risk of war in nuclear Asia |

| Economic | Reopens trade potential in Himalayas |

| Geopolitical | Reduces dependence on U.S./Russia balancing acts |

| National Pride | Both sides secure symbolic victories (Tawang for India, Aksai Chin for China) |

| Global Image | Enhances credibility as responsible great powers |

🚫 Risks & Obstacles

-

Hardliner backlash in both countries.

-

Military-industrial resistance to peace dividend.

-

Political risk of appearing “soft” on territorial claims.

-

Fear of betrayal (especially in light of Galwan 2020).

✅ Enablers for Success

-

High-level leadership convergence (Xi–Modi or successors).

-

Civil society and academic track-2 diplomacy.

-

Regional momentum from multilateral institutions (e.g., SCO, BRICS).

-

Support from neutral third parties (e.g., Norway, Switzerland) as facilitators.

-

Public messaging strategy to prepare both populations for a pragmatic peace.

🕊️ Closing Thought:

“Mountains divide us, but history, faith, and the future bind us. India and China must not remain prisoners of the past.”

🧵 How India & China can finally resolve their long-standing border dispute — a phased roadmap rooted in realism, trust-building, and strategic compromise. 👇

— Paramendra Kumar Bhagat (@paramendra) June 11, 2025

Trump’s Default: The Mist Of Empire (novel)

The 20% Growth Revolution: Nepal’s Path to Prosperity Through Kalkiism

Rethinking Trade: A Blueprint for a Just and Thriving Global Economy

The $500 Billion Pivot: How the India-US Alliance Can Reshape Global Trade

Trump’s Trade War

Peace For Taiwan Is Possible

Formula For Peace In Ukraine

The Last Age of War, The First Age of Peace: Lord Kalki, Prophecies, and the Path to Global Redemption

AOC 2028: : The Future of American Progressivism

No comments:

Post a Comment