Is the Chinese Political System a Meritocracy? A Case for the Argument

When people think of political meritocracy, China might not be the first country that comes to mind. It’s often described as authoritarian, opaque, or top-down. But peel back the layers, and one finds a complex, hierarchical political structure that prizes competence, long-term performance, and technocratic skill—arguably more so than many electoral democracies. In this blog post, we’ll explore the case for why China’s political system can be considered a meritocracy.

1. The Cadre Promotion System: Climbing the Ladder Through Performance

At the heart of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) system is a bureaucracy where advancement is based on track record, not popularity. Party members begin at local levels and must work their way up through township, county, provincial, and eventually national levels. Promotions are tied to the ability to deliver economic growth, maintain social stability, and meet central policy targets.

Unlike in many democracies, where a single charismatic campaign or media surge can propel someone to the highest office, Chinese officials often spend decades moving up the ranks. Xi Jinping himself spent years governing rural provinces like Hebei and Fujian before reaching the top. The system is structured to reward not only loyalty but also proven administrative capability.

2. Technocratic Governance: Engineers Over Ideologues

China has been governed for decades by technocrats—leaders with backgrounds in science, engineering, and economics. The majority of senior CCP leaders have advanced degrees and extensive administrative experience. In fact, China has one of the highest concentrations of PhDs among top government officials.

This technocratic orientation is reflected in long-term planning documents like the Five-Year Plans and in the implementation of ambitious infrastructure and technological goals. Whether one agrees with their policies or not, Chinese leaders are rarely political novices. They are seasoned administrators and planners, groomed over years to think in systemic, data-driven terms.

3. Policy Continuity and Strategic Vision

Democracies often suffer from electoral short-termism—what's popular for the next election, not what’s right for the next decade. China’s political system, insulated from election cycles, enables leaders to pursue long-range policies with consistency. Programs like the Belt and Road Initiative or the Made in China 2025 plan are multi-decade efforts with clear metrics and phased implementation. Such sustained policy execution is difficult without a trained and competent bureaucracy.

Meritocracy here doesn’t mean infallibility, but it does mean that policy is designed and implemented by people with subject-matter expertise, not just political capital.

4. Anti-Corruption and Internal Evaluation

Since coming to power, Xi Jinping has waged a sweeping anti-corruption campaign that has disciplined or removed over 1.5 million officials. While some critics see this as a political purge, many observers agree it has also raised the bar for administrative integrity. Internal CCP evaluations are intense, with data audits, peer reviews, and local satisfaction surveys contributing to promotion decisions.

An official who fails to meet local development goals or is found incompetent is unlikely to advance. Internal feedback mechanisms, although opaque to outsiders, are very real and rigorous within the system.

5. Public Input Without Direct Elections

Contrary to common belief, China’s political system does include mechanisms for citizen feedback. The central government conducts nationwide surveys, collects big data on public sentiment via digital platforms, and tests policy in pilot cities before scaling. This blend of experimentation, feedback, and adaptation allows Chinese leaders to be responsive even without direct electoral accountability.

It’s a different form of legitimacy—performance-based rather than vote-based. And when performance metrics are met, especially in areas like poverty reduction, infrastructure delivery, or technological innovation, the system’s legitimacy is reinforced.

Conclusion: A Different Kind of Meritocracy

China’s political meritocracy is not without flaws—lack of transparency, limited public dissent, and censorship are real and valid concerns. But dismissing the entire system as merely authoritarian overlooks a crucial reality: the Chinese state is run by an elite that, for the most part, has proven its competence over time and risen through a structured merit-based system.

In contrast to systems that prioritize popularity, fundraising, or ideology, China’s model puts a premium on institutional experience, technocratic ability, and delivery of results. Whether one supports or opposes this model, it deserves recognition as an alternative mode of governance—one that claims legitimacy not through ballots, but through outcomes.

Further Reading

-

Daniel A. Bell’s The China Model: Political Meritocracy and the Limits of Democracy

-

Cheng Li’s work at Brookings on leadership transitions in China

-

Reports on CCP’s cadre evaluation system by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

China: A Modern Autocracy Disguised in Bureaucratic Rigor

Since the founding of the People's Republic in 1949, China has operated under the absolute control of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). While some describe the system as meritocratic, the undeniable truth remains: China is, and has always been, an autocracy—one where power is centralized, dissent is suppressed, and political pluralism is absent. In this blog post, we’ll outline why China’s political system remains fundamentally autocratic, regardless of its administrative complexity or economic performance.

1. Single-Party Rule: No Competition, No Choice

At the core of any democracy is political competition. China, by design, eliminates this entirely. The CCP has maintained an unbroken monopoly on political power since 1949. There are no meaningful elections for national leadership. Citizens cannot vote out the ruling party, criticize it openly, or form independent opposition parties. All seven members of the Politburo Standing Committee—the country’s highest decision-making body—are selected behind closed doors, not by voters.

The absence of political pluralism is the defining trait of an autocracy. In China, power flows from one party and one party alone.

2. Lack of Press Freedom and Civil Liberties

China routinely ranks near the bottom in global press freedom indices. Independent journalism is heavily censored, foreign reporters face increasing restrictions, and Chinese citizens who post dissenting views online are routinely surveilled, detained, or imprisoned.

Freedom of speech, association, and assembly—pillars of any open society—are denied. The 2015 "709 crackdown" on human rights lawyers, the detention of journalists during the COVID-19 outbreak, and the disappearance of whistleblowers all reveal a system that views freedom as a threat, not a right.

Autocracies don’t allow space for public dissent. China’s tight control of information confirms its autocratic nature.

3. A Cult of Leadership, Not Institutional Democracy

China has a long history of strongman politics—first under Mao Zedong, then briefly tempered under Deng Xiaoping’s more collective leadership model. But in recent years, President Xi Jinping has consolidated power to an extent unseen since Mao.

In 2018, China abolished presidential term limits, allowing Xi to rule indefinitely. His name and political ideology—Xi Jinping Thought—have been enshrined in the constitution, studied in schools, and invoked in every major policy speech. This personalization of power is textbook autocracy.

Rather than a rule of law, China practices rule by leader.

4. Opaque Governance and Lack of Accountability

China’s decision-making process is shrouded in secrecy. The CCP's top bodies deliberate in private, without public oversight, transparency, or media access. Citizens have no way to hold leaders accountable through judicial review, legislative inquiry, or the ballot box.

Autocracies rely on centralized, opaque authority—and China exemplifies this with a governance structure that demands loyalty, not accountability.

Even when policies fail (as seen in the early mishandling of COVID-19 or harsh zero-COVID lockdowns), there are no public reckonings. Internal party loyalty takes precedence over public responsibility.

5. Repression in the Name of “Stability”

From the crackdown in Tiananmen Square in 1989 to the internment of over a million Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang, the Chinese state has repeatedly used mass repression to maintain its grip on power.

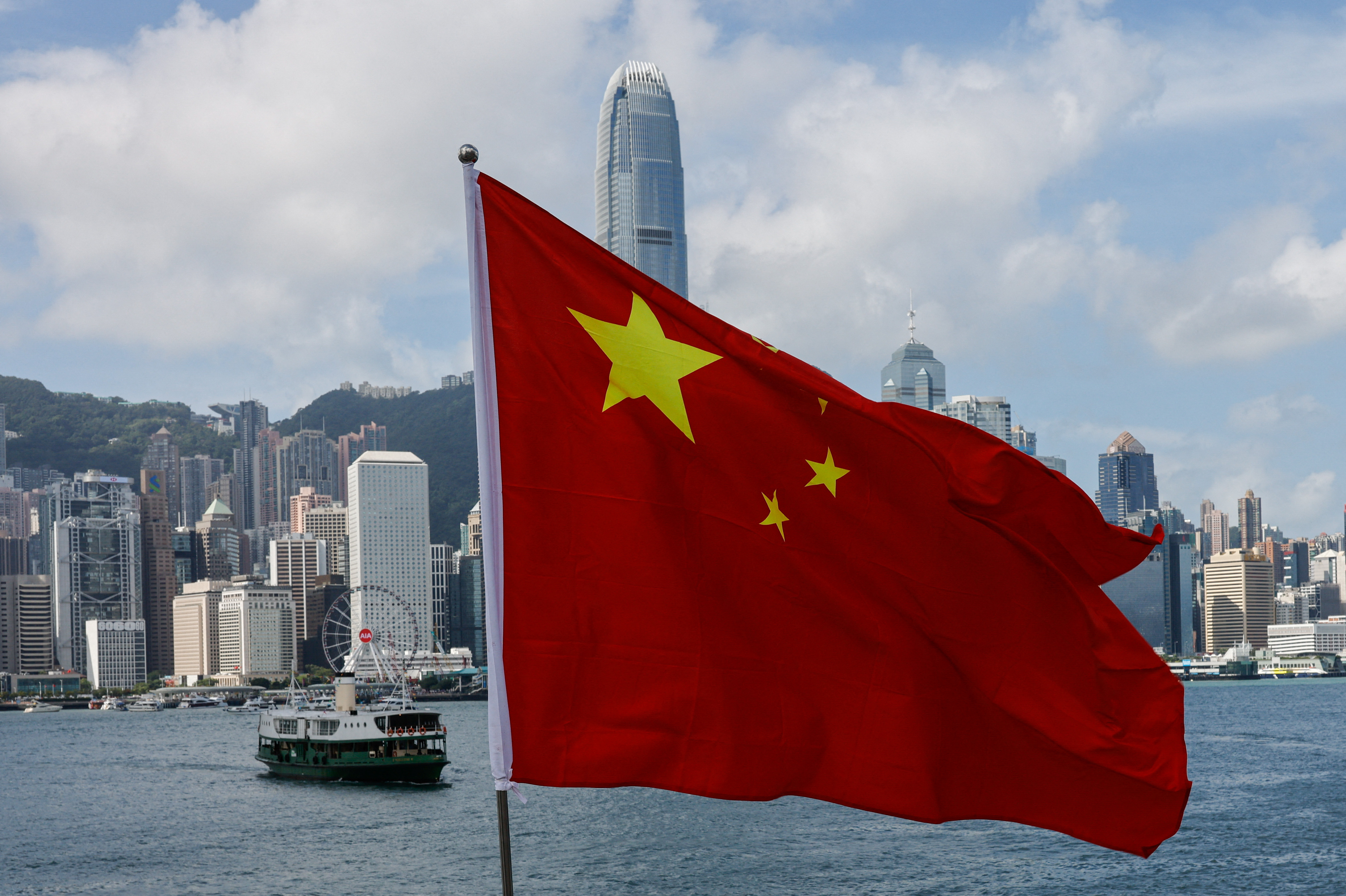

In Hong Kong, the promise of “One Country, Two Systems” was gutted by the National Security Law of 2020, which criminalized dissent and led to the closure of newspapers, the arrest of pro-democracy activists, and the silencing of civil society.

An autocracy isn’t just defined by how leaders are chosen—it’s defined by how power is preserved. In China, repression is a feature, not a bug.

6. No Real Checks and Balances

There is no independent judiciary in China. Courts serve the party. The military answers to the CCP, not to the state or people. Legislatures, like the National People’s Congress, act as rubber stamps rather than deliberative bodies.

A system without institutional checks is not just undemocratic—it is autocratic. All power in China ultimately flows upward to a single apex: the CCP leadership.

Conclusion: Administrative Efficiency Doesn’t Equal Political Freedom

While China’s government is often described as efficient, technocratic, or even meritocratic, these traits do not negate its autocratic nature. A competent bureaucracy does not make a regime democratic. The absence of political competition, civil liberties, and public accountability is conclusive.

China today is not transitioning toward democracy; it is deepening its authoritarian model. The fusion of surveillance technology, censorship, and centralized leadership is creating a 21st-century autocracy—smarter, faster, and more data-driven, but no less repressive.

To mistake this for meritocracy is to confuse method with morality. What China has built is not a meritocracy—it is an autocracy with performance metrics.

Further Reading

-

Freedom House’s Annual Reports on China’s Freedom Score

-

Human Rights Watch reports on repression in Xinjiang and Hong Kong

-

The Party: The Secret World of China’s Communist Rulers by Richard McGregor

China's Political System: Between Meritocracy and Autocracy — The Case for Reform

China’s political system defies easy labels. It has elements of both meritocracy and autocracy, blending technocratic governance with strict one-party control. The Communist Party of China (CCP) governs over 1.4 billion people with a model that has delivered remarkable economic results and lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty—yet it has also drawn widespread criticism for repressing dissent, lacking transparency, and concentrating power in a closed elite.

In this synthesis, we examine both sides of the debate—China as a meritocracy and China as an autocracy—and explore what meaningful political reform could look like in a uniquely Chinese context. We argue that reform is not only possible without dismantling one-party rule, but may be necessary to maintain long-term stability and global legitimacy.

The Case for Meritocracy

-

Bureaucratic Skill Over Popularity

China’s officials must climb through years of service, often starting at the local level. Their promotions are based on performance in metrics like GDP growth, infrastructure delivery, and policy execution. In this sense, China’s political class is trained, vetted, and evaluated—unlike many democracies where electoral charisma can sometimes outweigh competence. -

Technocratic Governance

Engineers, economists, and policy wonks dominate the leadership ranks. China’s government plans decades ahead and executes mega-projects like high-speed rail, urbanization, and green energy at breakneck speed. Data-driven feedback loops and digital experimentation zones (like Shenzhen) add to this technocratic strength. -

Poverty Reduction and Economic Planning

China's centralized system enabled an unprecedented, state-led campaign to eradicate extreme poverty. The success of this effort underscores the potential of a meritocratic apparatus when aligned with national goals.

The Case for Autocracy

-

No Electoral Legitimacy or Political Competition

The CCP allows no alternative parties or competitive national elections. Political power is concentrated at the top, and the general public has no formal say in leadership transitions or national policy direction. -

Censorship and Control

Freedom of speech, media, and assembly are heavily restricted. Social credit systems, mass surveillance, and repression in regions like Xinjiang and Hong Kong are hallmarks of an authoritarian state. -

Personality Cult and Lifetime Leadership

The removal of term limits for Xi Jinping in 2018 marked a regression in institutionalization. China has tilted from collective leadership back toward strongman politics, a trend that increases the risks of internal stagnation and public discontent.

A Balanced View: Dynamic but Rigid

China’s political system is effective but brittle. It produces competent administrators, but limits public feedback and constrains innovation in civil society. It executes policy with precision, but often without consent. This mix of strengths and weaknesses means that while China has outperformed many peers economically, its system faces internal pressures that could make future reform essential.

Why Reform Is Necessary—and Possible

-

Performance Legitimacy Isn’t Forever

The CCP’s legitimacy currently rests on its performance—growth, jobs, national pride. But what happens when growth slows, inequality rises, or global crises emerge? Without channels for grievance and adaptation, discontent can fester beneath the surface. -

Capitalism Has Already Altered the Foundation

China today is not a communist economy in any traditional sense. Markets, private property, entrepreneurship, and billionaires are pillars of the system. The ideological core has already shifted. Political reforms wouldn’t be the first major transformation—economic reforms were. -

The CCP Has Considered Reform Before

In the 1980s, Deng Xiaoping’s reforms included internal debate over separating Party and state, rotating leadership, and institutionalizing checks to prevent Mao-style excess. Although these efforts largely stalled post-Tiananmen, they show that reform has long been part of the CCP’s internal discourse.

What Political Reform Might Look Like (Within One-Party Rule)

-

Intra-Party Democracy

Open up CCP internal elections to greater competition and transparency. Allow multiple candidates for Party leadership roles, encourage debates, and let rank-and-file members have a voice. -

Independent Judiciary

A judiciary that is loyal to the Constitution, not just the Party, would offer rule of law protections while maintaining Party rule at the top. -

Decentralized Governance

Empower local governments with greater autonomy to experiment with policies, thus creating a laboratory of democracy without national-level pluralism. -

Public Feedback Mechanisms

Formalize channels for public petitions, deliberative councils, and citizen juries on key issues. This is already happening in limited forms—scale it up. -

Media Freedoms Within Boundaries

Allow a professional, independent press to report on corruption, pollution, and mismanagement. This would strengthen the system by exposing flaws early. -

Reinstitute Term Limits

Re-establishing leadership turnover rules would reduce the risk of power monopolies and signal a return to institutional governance.

Political Reform as Evolution, Not Revolution

Reform does not have to mean Western-style liberal democracy. In fact, the most sustainable path for China may be gradual evolution within the framework of one-party rule. China can modernize politically just as it did economically—pragmatically, cautiously, and in its own way.

If reforms focus on governance quality, rights protection, and institutional resilience rather than on importing foreign models, they may even strengthen the CCP’s legitimacy. The goal need not be to abandon one-party rule, but to improve the Party’s responsiveness, adaptability, and moral authority.

Conclusion: The Reform Imperative

China’s political system is a paradox of efficiency and repression, of talent and control. The CCP's strength has always been its ability to adapt. That adaptability now demands political reform. Without it, the risks of stagnation, resistance, and legitimacy crisis grow.

The tools are already in China’s hands: data, talent, economic dynamism, and a long tradition of statecraft. Reform is not a concession to the West; it’s an investment in China’s own future. A more open, resilient, and participatory system would not weaken China—it would unleash its full potential.

Further Reading

-

The China Model by Daniel A. Bell

-

From Deng to Xi: Economic Reform and the Limits of Authoritarian Adaptation by Barry Naughton

-

Brookings Institution papers on intra-party reform and governance innovation in China

China: Meritocracy? Autocracy? 🧵👇

— Paramendra Kumar Bhagat (@paramendra) June 3, 2025

The 20% Growth Revolution: Nepal’s Path to Prosperity Through Kalkiism

Rethinking Trade: A Blueprint for a Just and Thriving Global Economy

The $500 Billion Pivot: How the India-US Alliance Can Reshape Global Trade

Trump’s Trade War

Peace For Taiwan Is Possible

Formula For Peace In Ukraine

The Last Age of War, The First Age of Peace: Lord Kalki, Prophecies, and the Path to Global Redemption

AOC 2028: : The Future of American Progressivism

Velocity Money: Crypto, Karma, and the End of Traditional Economics

The Next Decade of Biotech: Convergence, Innovation, and Transformation

Beyond Motion: How Robots Will Redefine The Art Of Movement

ChatGPT For Business: A Workbook

Becoming an AI-First Organization

Quantum Computing: Applications And Implications

Challenges In AI Safety

AI-Era Social Network: Reimagined for Truth, Trust & Transformation

Remote Work Productivity Hacks

How to Make Money with AI Tools

AI for Beginners

No comments:

Post a Comment