America’s Dysfunctional Pillars: Bureaucracy, Fraud, and Fiscal Ruin in Healthcare, Defense, and National Debt

In an era where the United States prides itself on innovation, entrepreneurial vigor, and market-driven efficiency, a closer look beneath the surface reveals a starkly different story. Beneath the gleaming towers of Silicon Valley and Wall Street, America’s key institutions—healthcare, defense, and fiscal management—are entangled in a web of inefficiency, fraud, and misaligned incentives. Like a high-tech ship with a leaky hull, resources are drained while the nation sails toward crises in public health, national security, and economic stability.

These dysfunctions echo historical collapses, from the Soviet Union’s bureaucratic quagmire to the Mongol Empire’s fiscal misadventures, showing how systemic flaws can undermine even the most formidable civilizations.

The Soviet-Style Mess of U.S. Healthcare

U.S. healthcare, long criticized for its complexity, has evolved into a labyrinthine system reminiscent of Soviet bureaucracies: layers of administration multiply costs without improving outcomes. With annual spending approaching $4.3 trillion—nearly 18% of GDP—estimates suggest that up to 10% is lost to fraud and abuse, translating into hundreds of billions of dollars siphoned away from patient care.

Fraud takes many forms: upcoding procedures, billing for services never rendered, or recommending unnecessary treatments. Each act erodes public trust and diverts funds from genuine care. Underlying these issues are deeply misaligned incentives. The fee-for-service model rewards volume over value, encouraging over-treatment while insurers and government programs, including Medicare, struggle with inflated reimbursements. For instance, Medicare Advantage plans have been accused of inflating patient risk scores to secure higher payments, costing taxpayers billions.

Yet political narratives often simplify the problem as "waste, fraud, and abuse," masking structural flaws. Medicaid’s open-ended federal matching, for example, incentivizes states to expand coverage without necessarily improving efficiency, creating perverse incentives that reward bureaucracy over outcomes.

Layered atop this are environmental and societal factors fueling chronic disease. Corporate food production, rich in processed ingredients, disrupts the gut microbiome, promoting obesity, inflammation, and metabolic disorders. Studies show altered gut bacteria in obese individuals extract more energy from food while impairing metabolism, turning ordinary diets into obesity traps.

Despite this, mainstream media and political rhetoric often stigmatize individuals, framing obesity as a matter of personal responsibility rather than the systemic effects of industrialized food, urban design, or socio-economic conditions. The result? Over 40% of U.S. adults are obese, straining a healthcare system already buckling under administrative inefficiency and misaligned incentives.

Defense Spending: A Black Hole of Fraud and Unaccountability

The Department of Defense (DoD), America’s second dysfunctional pillar, devours over $800 billion annually, yet basic financial transparency remains elusive. In 2025, for the eighth consecutive year, the Pentagon failed its department-wide audit, unable to verify trillions in assets due to outdated systems and weak internal controls.

While not all failures are fraudulent, the systemic opacity mirrors the inefficiencies of the Soviet military-industrial complex, where massive budgets masked waste. Documented fraud within the DoD reached $10.8 billion from 2017 to 2024 alone, including contractor overbilling, inaccurate inventory forecasting, and inefficient management of spare parts. Hundreds of millions in government property provided to contractors go unaccounted for, creating fertile ground for abuse.

Efforts to clean up are slow. Only the Marine Corps has recently passed an audit, and while promises of full audit compliance by 2028 exist, progress lags. The lack of accountability not only wastes resources but undermines national security, as the Pentagon cannot reliably track what it owns or spends.

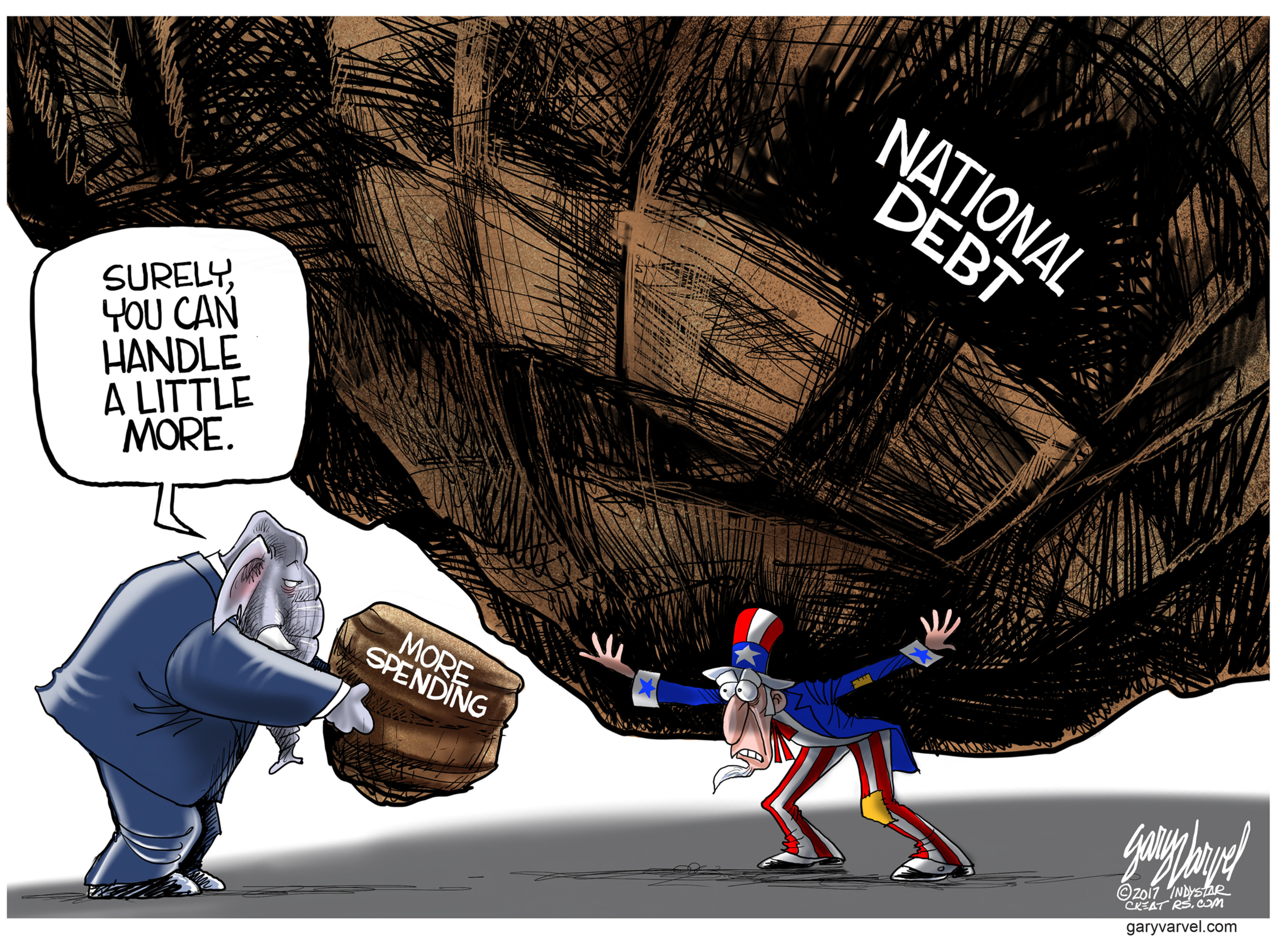

Capitol Hill’s Debt Bomb: Lessons from the Mongols

The third pillar, fiscal management, presents a crisis of its own. As of January 2026, U.S. national debt stands at roughly $38.5 trillion, an increase of $2.25 trillion in a single year—growing at an astonishing $8 billion per day. Interest payments alone consume nearly 19% of federal spending in FY 2026, leaving less fiscal space for essential services or emergency responses.

Annual deficits exceed $1 trillion, driven by entitlement growth, rising interest obligations, and unfettered borrowing. This trajectory echoes the fiscal collapse of the Mongol Empire under Kublai Khan, where over-issuance of silver-backed paper currency led to rampant inflation, civil unrest, and eventual collapse by 1368. Like the Yuan Dynasty, modern America risks eroding the value of its currency and destabilizing its economy if structural reforms are not enacted.

Toward Fundamental Reform

The convergence of bureaucratic bloat in healthcare, fraud-laden defense spending, and ballooning national debt forms a toxic triad threatening America’s stability. Ignoring misaligned incentives and failing to enforce accountability is akin to repeating historical mistakes.

Meaningful reform must tackle these pillars simultaneously: aligning healthcare incentives with patient outcomes, enforcing rigorous defense audits, and instituting fiscal discipline to curb deficit spending. Without such interventions, the United States risks a slow-motion unraveling, demonstrating that even the mightiest nations are vulnerable to the corrosive forces of inefficiency, corruption, and financial imprudence.

History is not just a teacher; it is a warning. America stands at a crossroads: continue down the path of systemic dysfunction, or embrace bold reform before bureaucracy, fraud, and debt become the architects of national decline.

The Economic Collapse of the Mongol Empire: Hyperinflation, Over-Issuance, and Systemic Failure

At its zenith under leaders like Genghis Khan and Kublai Khan, the Mongol Empire was the largest contiguous land empire in history, stretching from the steppes of Eastern Europe to the Sea of Japan. Its military prowess and administrative innovations created a Pax Mongolica that facilitated trade, cultural exchange, and economic growth across Eurasia. Yet by the mid-14th century, the empire fractured and collapsed. While factors such as military overextension, internal strife, environmental degradation, and the Black Death contributed, economic mismanagement—particularly hyperinflation fueled by the overprinting of paper money during the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368)—proved emblematic of its downfall.

The Introduction of Paper Money: Innovation Under Kublai Khan

The Mongols inherited China’s early experiments with paper currency from the Song Dynasty. In 1260, after ascending as Great Khan, Kublai Khan introduced the zhongtong chao (中統鈔), the first paper money fully backed by silver. This ambitious system sought to unify a chaotic monetary landscape of inconvertible notes, copper, and iron coins, mandating paper as the sole legal tender.

For decades, this innovation facilitated trade across the vast empire, including along the Silk Road, linking East and West economically. The Yuan monetary system evolved in three stages:

Full silver convertibility (1260–1275): Notes could be fully exchanged for silver, maintaining stability with inflation around 4.5% annually.

Nominal silver convertibility (1276–1309): Silver shortages made convertibility inconsistent, yet inflation remained moderate (~1.8%).

Fiat standard (1310–1368): The silver link was abandoned, turning currency into pure fiat money backed solely by government decree. This unleashed uncontrolled issuance, laying the groundwork for hyperinflation.

For nearly fifty years (1290–1340), prices remained relatively stable, demonstrating that, in a pre-modern economy, paper currency could succeed—if carefully managed. But fiscal pressures from wars, public works, and rebellions soon forced the Yuan government to over-issue notes.

Drivers of Hyperinflation: War, Deficits, and Overprinting

The Yuan’s reliance on seigniorage—the profit generated from printing money—was central to the economic collapse. Massive expenditures included:

Costly military campaigns: Failed invasions of Japan and Southeast Asia drained resources.

Grand infrastructure projects: Expansion of the Grand Canal, construction of capitals in Beijing (Daidu) and Shangdu (Xanadu), and maintenance of extensive postal networks.

Suppression of rebellions: Civil wars and uprisings, particularly in later years, required continual military spending.

By 1310, the Yuan had issued roughly 36.3 million ding (a unit of account), far exceeding reserves. Inflation surged, averaging 11% annually between 1340 and 1355. By 1309, notes had depreciated by a staggering 1000% compared to 1260 levels. Subsequent issues, like the zhizheng jiaochao (至正交鈔) of 1350, fared no better, leading some regions to revert to barter.

Heavy taxation compounded the crisis, sparking social unrest and economic stagnation. The mid-14th century Black Death further disrupted trade and agriculture, amplifying the downturn.

Broader Economic Impacts and Fragmentation

Hyperinflation undermined trust in the Yuan currency, eroding the Pax Mongolica and destabilizing trade networks that had once connected Eurasia. Silk Road routes fragmented as the empire’s khanates—the Golden Horde, Chagatai Khanate, Ilkhanate, and Yuan—pursued independent policies after Kublai’s death in 1294. Economic interdependence waned, reducing prosperity across the continent.

In China, economic distress fueled peasant uprisings, culminating in the Red Turban Rebellion (1351–1368). Zhu Yuanzhang eventually overthrew the Yuan, founding the Ming Dynasty in 1368. Elsewhere, the Ilkhanate disintegrated by 1353, and the Golden Horde dissolved over the following century. The Mongol Empire’s territorial cohesion collapsed alongside its monetary stability.

Lessons from the Collapse

The Yuan Dynasty’s economic downfall demonstrates how innovative policies, such as fiat currency, can backfire without fiscal discipline and institutional oversight. Overprinting to fund wars, public projects, and lavish expenditures created a cycle of inflation, social unrest, and collapse—foreshadowing later hyperinflations in Europe, Latin America, and Weimar Germany.

Despite its initial success, the lack of checks and balances allowed short-term gains to undermine long-term stability. The Mongol Empire’s story is a timeless cautionary tale: even the most formidable political and military power is vulnerable when economic foundations are ignored. In the delicate balance between innovation and prudence, fiscal mismanagement can be as lethal as any foreign enemy.

The Fiscal Decline of the Roman Empire: Inflation, Taxation, and the Path to Collapse

The Roman Empire, once a beacon of economic prosperity and military might, faced a prolonged fiscal decline that profoundly contributed to its eventual fall in the 5th century CE. This was not a sudden catastrophe but a gradual unraveling—a slow corrosion of financial stability fueled by currency debasement, hyperinflation, excessive taxation, military overexpansion, and systemic corruption. While barbarian invasions and external pressures accelerated the collapse, it was the empire’s internal fiscal mismanagement that weakened its foundations, leading to economic stagnation, social unrest, and political fragmentation.

Currency Debasement: The Erosion of Monetary Value

One of the clearest signals of Rome’s economic deterioration was the progressive debasement of its currency, particularly the silver denarius. Starting in the 1st century CE under emperors such as Nero, the silver content in coins was systematically reduced to stretch limited reserves. By the 3rd century, under rulers like Aurelian, the denarius contained almost no silver, replaced entirely by base metals such as copper.

This strategy allowed the state to mint more coins to fund escalating military and administrative costs, but it triggered runaway inflation. Hyperinflation peaked during the 3rd century, with prices for essentials like wheat soaring. Ordinary citizens found themselves paying increasingly large quantities of debased coins for basic goods, while merchants often reverted to barter in regions where trust in currency had collapsed.

Rome’s reliance on seigniorage—profit from minting money—prioritized short-term revenue over long-term economic stability. Efforts to curb inflation through price edicts under Diocletian ultimately failed, further destabilizing trade and commerce.

Excessive Taxation and Government Overspending

Rome’s fiscal decline was inseparable from its oppressive tax system. During the Republic, taxes were modest (around 1–3% of GDP), supporting trade and investment. By the 3rd and 4th centuries, however, constant warfare, bureaucratic expansion, and administrative corruption led to soaring taxes on land, goods, and individuals.

The burden fell disproportionately on provincials and lower classes, as many Roman citizens in Italy enjoyed partial exemptions. Corruption in tax collection—bribes, arbitrary assessments, and exploitation by local officials—widened the wealth gap and fueled resentment.

Emperors such as Diocletian institutionalized in-kind taxation (food, labor, and services), disrupting markets and encouraging peasants to flee urban centers for self-sufficiency. Public spending ballooned on entitlements like free grain distributions and public games, resembling a rudimentary welfare state without sustainable funding. Property rights became insecure as emperors confiscated estates to reward loyalists, deterring investment and accelerating economic contraction.

Military Overexpansion: Rome’s Fiscal Achilles’ Heel

The Roman military, long the backbone of the empire, became its most expensive liability. At its peak, army expenditures consumed up to 75% of the state budget. Maintaining garrisons across vast territories—from Britain to the Euphrates—strained both finances and logistics.

By the 3rd century, persistent threats from Germanic tribes and the Sassanid Empire necessitated larger forces. Recruitment increasingly relied on less reliable barbarian mercenaries, paid in gold, which further depleted imperial reserves. Civil wars and unstable successions compounded the problem, as emperors sought to secure loyalty with lavish bonuses and pay raises.

The empire’s inability to plunder new territories after the 2nd century CE removed a critical revenue stream, forcing dependence on internal taxation and debased currency—a financial trap from which there was little escape.

Economic Stagnation and Social Factors

Rome’s economic malaise was reinforced by structural and social factors. Overreliance on slave labor stifled innovation, while the wealthy elite monopolized vast latifundia, leaving small farmers struggling. Plagues, including the Antonine Plague (165–180 CE), reduced population and labor supply, shrinking the tax base.

Trade declined as inflation eroded purchasing power and insecurity disrupted transportation networks. Urban centers, once thriving hubs of commerce, emptied as populations sought refuge in rural areas, resulting in localized economies and diminished specialization. Climatic shifts—from the warm Roman Climatic Optimum to cooler conditions—may have further strained agricultural production.

Consequences: From Crisis to Collapse

By the 4th century, the Western Roman Empire’s economy had fragmented, with regions operating semi-independently. The state’s fiscal capacity crumbled, leaving defenses underfunded and inviting invasions. Social unrest—manifested in uprisings like the bagaudae rebellions—further weakened cohesion.

The sack of Rome in 410 CE and the fall of the Western Empire in 476 CE marked the culmination of these economic and social stresses. The Eastern Byzantine Empire persisted longer due to comparatively stronger fiscal management, illustrating the critical link between sound financial institutions and political survival.

Lessons for Modern Economies

Rome’s fiscal decline offers enduring lessons: unchecked military spending, currency manipulation, and inequitable taxation can erode even the mightiest empires. Parallels to contemporary issues—debt crises, inflation, and systemic corruption—underscore the need for balanced budgets, secure property rights, and adaptive policy frameworks.

History also demonstrates the cost of delayed intervention. As seen with Tiberius’ credit policies in 33 CE, timely fiscal adjustments can avert disaster—but Rome’s leaders often failed to act decisively, sealing the empire’s fate. The Roman story is a cautionary tale for modern states: power and conquest cannot compensate for unsound financial foundations.